We kindly inform you that, as long as the subject affiliation of our 300.000+ articles is in progress, you might get unsufficient or no results on your third level or second level search. In this case, please broaden your search criteria.

In the 1920s Le Corbusier propagated some rules that led to building up cities solely subordinated to the functional aims. The tradition of concentrating the building complex around the edifices important in cultural or spiritual life was ignored. Le Corbusier’s principles were present until the 1970s, despite the long-lasting critical estimation. According to these guidelines the town of Évry was established as one of many towns surrounding Paris, with the function of protecting the capital city of France against its extensive growth. The town without a centre changed under the influence of the inhabitants. Populated with immigrants it started to be marked with the buildings that enforced the cultural identity of the particular groups. The erection of a mosque and a synagogue gave the local urbanists the reason to think of building a large cathedral in the logical centre of the town. Initially the intention did not gain the local bishop’s approval, for the pastoral concepts of evangelisation were based on far less spectacular forms. Hence the ideological factors decided the erection of the cathedral, among them the tiredness of modernism and the will to come back to pre-modern tradition of shaping the city. The building of the great cathedral was supposed to remind the old French tradition of erecting cathedral edifices. In new reality however, when the town is inhabited by the people so varieted ethnically and religiously, the postmodern cathedral occured to be the work equally distant from the tradition as the modern surroundings.

More...

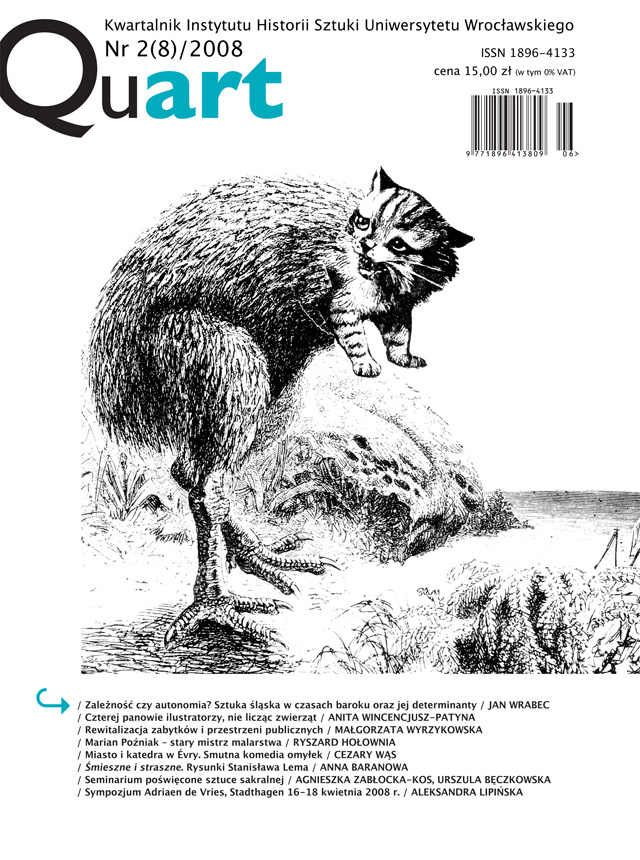

The text was written in the relation to Stanisław Lem’s (1921-2006) drawings exhibition held in Wiesław Dyląg’s gallery in Cracow (Galeria dylag.pl) this spring. The renowned writer and thinker, the world leading creator of science-fiction showed his less-known face. The two original drawing cycles were presented: one of the post-war period and another from the time of his mature creation. The first one, completely unknown, is a set of satirical variations on the theme of the contest for a design of Frederic Chopin monument, held in Cracow within The Chopin Year – 1949. The latter consists of the author’s drawings for his famous novel ‘Star Diaries’ from the turn of the 1960s (for the first time the full version was edited by the ‘Czytelnik’ publishing house as its fourth edition in 1971). Stanisław Lem – a draughtsman using a light and natural style, can be situated among the creators of a grotesque satire, bizarre monsters and horrors. The drawings of a mainly linear character, were produced with a dark felt-tipped or a ballpoint pen on ordinary paper or bristol sheets. Each of them has an autonomous artistic value and at the same time comes as a perfect comment to the author’s writings.

More...

Between 17th February and 1st March 2008 six students with Dr Agnieszka Zabłocka-Kos from the History of Art Institute at the University of Wrocław took part in The International Interdisciplinary Seminar entitled ‘Religion in the Modern World. Sacral Architecture in Central Europe in the Years 1890-1930’. The main organisers were: Prof Michaela Marek from Institut für Kunstgeschichte (The University of Leipzig) and Prof Martin Schulze Wessel from Lehrstuhl für Osteuropäische Geschichte (The University in Munich) in co-operation with the History of Art Institute at the University of Wrocław (Dr Agnieszka Zabłocka-Kos), History of Art Institute at The Jagiellonian University, Cracow (Prof Wojciech Bałus) and Katedra Německých a Rakouských Studií from Charles University in Prague (Dr Miroslav Kunstat). Twenty-five students and five academic supervisors took part in the seminar. A fortnight travel through Central Europe was divided into three-day stays in Berlin, Leipzig, Wrocław, Cracow and Prague. The aim of the international seminar was to ‘build bridges’, both between the three nations: the Poles, the Germans and the Czechs and between the disciplines: art historians, historians and German affairs specialists. During the discussions and sightseeing sessions the participants had the possibility to get acquainted with the variety of sacral art around 1900 and in the first half of the twentieth century with the background of the complicated social, historical, religious and theological situations in Germany, Poland and Bohemia of those days. The publication of the students’ best papers in „Dzieła i Interpretacje” journal, edited by the students of history of art in Wrocław, will come as a material result of the meeting.

More...

Both in Greek and Roman ancient times and Judaism, ‘prophetic’ dreams used to have an important political function. A great role was still ascribed to them in the Christian Middle Ages, what can be seen best in the example of the iconography of two ‘founder’s legends’: one of Santa Maria Maggiore basilica in Rome (Filippo Rusuti’s mosaics on the facade, 1295) and the other one of the Franciscan Order (Giotto’s frescoes in the Upper Church at Assisi, ca. 1300). The Emperor Charles IV of Luxembourg had also – in his youth – ‘political’ dreams, translated into the language of pictorial presentations. At the dawn of an early modern era the dream visions, connected both with common political-religious disorders of the time of the Reformation and the peasant wars (Albrecht Dürer‘s watercolour of Dream of the Great Deluge, 1524) and with some particular political events, e.g. the defeat of the protestant princes of the Reich in the Battle of Mühlberg (Lucas Cranach the Younger’s woodcut engraving of Dream of Filip Melanchton, 1547), became fixed in painting and graphic art. However, we may speak about a remarkable role of ‘dreams’ no sooner as in the period preceding the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War and of its duration. The propaganda of the both fighting sides reached for a motif of a dream and a dream vision of some important political figures: the protestant Union (Dream of the Saxon Elector Friedrich the Wise, 1617; Dream of the Saxon Elector Johann Georg I, 1631) as well as the catholic League (Dream of King Ferdinand II, 1620). A few works of painting and graphic art of the sixteenth century, entitled as ‘dreams’, may be defined, according to the latest research, as ‘presumed dreams’. It applies both to Domenikos Theotokopoulos’s, called El Greco, painting from Escorial (1576-1579), entitled Dream of Philip II of Spain, which actually appears to be an allegorical Adoration of the Name of Jesus, and the two copper engravings of Dream of Raphael one by Marcantonio Raimondi (1506-1508) and the other by Giorgio Ghisi (1561). The latter, already with a new title Allegory of Human Life, might include some allusions to political situation of France after the King Henry II’s death. As such, it could have come as a political manifesto of the supporting party of the queen-widow, Catherine de Médicis. Still at the beginning of the eighteenth century the motifs of dreams, strictly connected with mediaeval tradition, were used by the Catholic Church fighting against ‘heresy’. Cosmas Damian Asam’s frescoes on the ceiling of the Cistercian church nave in Fürstenfeld near Munich (1723-1731) depicted ‘A white dog expelling the Church enemies’, referring to St. Bernard’s of Clairvaux gravid mother’s dream of the birth of a white dog. Later, in the period of the Enlightenment, a barking dog appearing in someone’s dream, certainly would not be regarded as ‘God’s omen’, but as ‘a nightmare’ from Henry Fuseli’s paintings, or ‘a monster’ from Francisco Goya’s Caprichos, ‘produced’ by a mind plunged in a dream.

More...

Clothing as a symbol of position and financial status was a matter of concern for authorities and moralists who wanted everyone to be clad according to their place in society. The attire can be also a subject of art work like in the published on 4th July 1601 in a Gdańsk publishing house of Jacob Rhode album containing 20 woodcuts invented by Anton Möller, picturing a common dress for women from different conditions in Gdańsk.On each page there is shown a group of Gdańsk women citizens clothed in a way typical for Gdańsk in that period (which was inspired with a Spanish fashion). Every scene has a commentary in a form of Latin and German inscriptions describing the details of a representation. As we know the name of its inventor, the names of the printmaker and the author of poems remain undiscovered.The album is an example of so called Trachtenbüchern, cycles showing costumes from different parts of the world, that were popular in the 16th century. This late example of such works is unlike all the others sacrificed to one city and the dress of its women dwellers. It shows a synthetic vision of fashion in Gdańsk and the most characteristic types of women that we could meet on its streets. And so we see severe matrons, young ladies praying for a good husband, nannies and nurses with children, maids, all shown in typical for them situations. There are also depicted the most important moments from the 17th century women’s life such as wedding, baptism and funeral. Certainly, apart from the clothing, custom plays here a significant role.However the cycle is a homogeneous reflection of the women’s world in Gdańsk in the 17th century, it certainly has also a didactic meaning. It shows a proper way of clothing suitable for women from every condition.Reminiscences of Möller’s album are visible in The Apotheosis of Gdańsk by Isaack van den Block, A view from Königsberg by Joachim Bering from 1613 and in the 18th century cycle of prints Danziger Ausrufer by Matthäus Deisch.

More...

In the 14th century the kings of Bohemia could have probably used not only the castle on the river left bank, but also a burgher house facing the Eastern facade of the town hall. It was demolished in the 20th century. What can prove the identification of the building with the Bohemian kings’ house is a set of sculpted heraldic images deriving from the place, known from drawings, and one preserved element of the decoration, which is a pair of busts.The three shields showed: the emblem of the German Reich held by kneeling angels, situated in the middle, and the emblems of Bohemian Kingdom and the duchy of Wrocław bowing to the central one. They may be referred to Charles IV and Wen-ceslaus IV. The couple of male and female half-figures, leaning out of the window also belonged to the house’s set of sculpted decoration. The royal images of young Wenceslaus IV and his wife Johanna of Bavaria may be considered here. The heraldic context, iconography and some other examples of monumental images of this kind (Mühlhausen; Collegiate Church of Holy Cross, Wrocław) justifies the reasoning. The questions of style and local analogies allow us to date the sculptures at ca. 1375-1385.It may be supposed that the people connected with the circle of royal authority took care of the house in Wrocław. Similar buildings serving royal administrative and representative functions, situated in the city centres at that time, could also be found in Prague, Brno, Świdnica and Cracow.

More...

The following article is the first publication in Polish, in which one of the most important Lombardian Baroque artists, so far almost completely unknown in Poland, has been introduced in a closer approach. The starting point for analysing his work became the painting of Slaughter of the Innocents (ca. 1616) from the collection of Museo Diocesano in Milan, untypical as far as its composition is concerned, as it has no precedence in Italian art of early Baroque, with distinctive horizontal partitions intermingled with clearly accentuated diagonals. Mazzucchelli applied it also in his other painting of Abduction of Helen (at present in the collection of Colnaghi Gallery in New York) dated at ca. 1613, however the author does not agree with the date and moves it towards ca. 1620. Another painting discussed in the article, being an artistic exercise for the mentioned above works, is Mazzucchelli’s much earlier canvas with Jacob’s Struggle with the Angel (ca. 1610, Museo Diocesano in Milan). In its composition there reappears a horizontal dominant, which organises around it the inner structure of the painting. The author seeks the inspiration for this untypical composition of Slaughter of the Innocents from Milan in Guido Reni’s painting of the same subject (1611, Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna), where also appears a strong horizontal accent in the motive of clasping hands. Despite its stylistic differences, the iconographic analogies and applying a similar compositional type may indicate Mazzucchelli’s closer contacts with Bologna milieu.

More...

Works of architecture of the twentieth-century main trends differ not only in their obtained forms. A set of characteristic forms may be indicated for modernism, but even referring to this style historians of architecture avoided defining it basing only on visual aspects of these works. Postmodernism complicated to a great extent such attempts to define by opening itself to formal contradiction and complexity of the outer expression of the works. In approach to characterise modernism, postmodernism and deconstructivism it seems necessary to take into consideration also the ways of these trends’ authors and works’ reference to the possibility of treating architecture as a medium of meaning. The subsequent distinguishers apply to ascribing the function of shaping a define social order to architecture. Each trend differed additionally in its attitude towards tradition. The architects differed also in ascribing to technics a particular role in life of contemporary societies. In the circle of modernists it even came to attributing sacral power to technics, what naturally was rejected by postmodernists. The set of differences is completed by ascribing some architects the role of a social demiurge, with which other architects disagree, comprehending their activity exclusively in categories of a specialist or a representative of a particular profession.

More...

In the mid years of the 19th century the movement of ‘Christian art’ revival was formed in the German Catholic Church. In Wrocław of this time one can notice numerous interesting artistic undertakings of church origins, connected both with erecting new buildings and renovating, furnishing and decorating the already existing churches. Not many examples of the ‘Christian art’ revival in Wrocław have been preserved; they are also merely documented. St. Adalbert Church is an exception as we can make use of many archival photographs of it kept in the Herder Institute in Marburg, which document also the elements of its 19th-century decoration. These photos, as well as some other sources, were the basis for an attempt to reconstruct the not preserved 19th-century decoration of St. Adalbert Church. In the article there are presented: the neo-Gothic main altar of 1855 with Raphael Schall’s painting; two neo-Gothic side altars of the same time, one of them with a painting by Theodor Hamacher; the cycle of thirteen paintings of apostels by Schall, Hamacher, Carl Wohnlich and Heinrich König the Younger, released from the 1850s to 1872; Julius Schneider’s painting from around 1865 dedicated to the Baroque side altar and stained glasses made between 1865 to 1880s by Adolph Seiler’s atelier in Wrocław.

More...

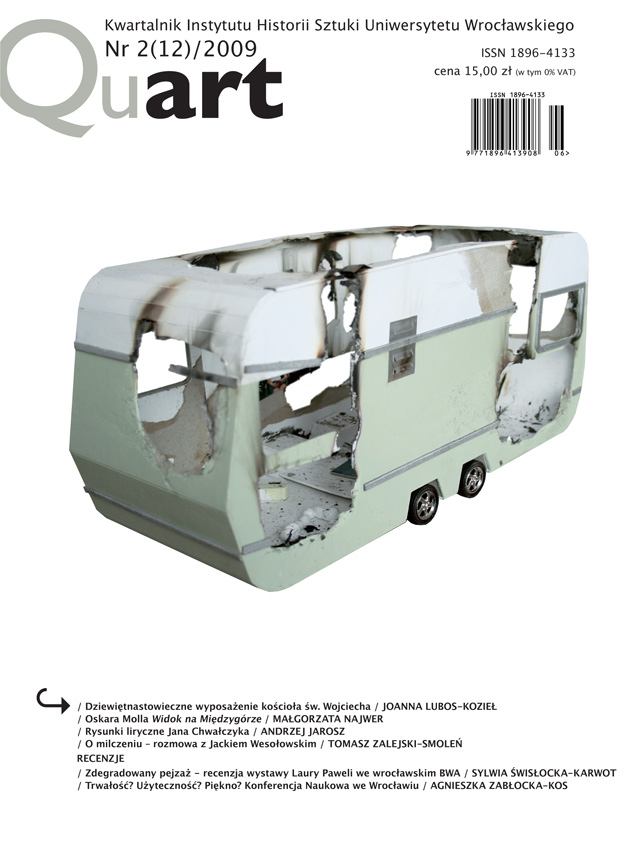

In spite of the expiry of over six decades from the last war, in spite of the damage which touched the Silesian art for that cause, still happily, albeit unexpectedly, are looming from darkness of the oblivion works important, sometimes outstanding. In the previous year I wrote about post-war fate of Percival and Grail Castle – of symbolist Hermann Hendrich’s brush – picture painted for the ‘Sagenhalle’ in Szklarska Poręba. In the beginning of this year in Wrocław collector’s circle there appeared a scheming, not-signed, preserved in an intact state, Fauvist view of a mountain town. Formal and comparative painting’s analyses lead to ambiguous conclusions. With respect to colour, composition and technique, the picture is fully identifying itself with Oscar Moll’s painting, especially with his output from years 1918 – 1920. The gouache is showing an extensive landscape of Międzygórze, seen from above, where the artist spent holidays in his own summer house. This outstanding author imprinted the mark of his personality not only on the artistic life of Wrocław, but much more widely – on the interwar German painting. Subtle intellectual, because of numerous travels liberal towards other cultures, recognizing the precursor significance of the contemporary French painting, Matisse’s friend and apologist, was entirely open to new streams and artistic achievements. His activity while holding the office of the director, led to the bloom of the academy in Wrocław which became then one of the best artistic colleges in Germany. After the takeover by the Nazis Oscar Moll’s art was regarded as degenerate, whereas the artist was banned from painting and exhibiting.

More...