Keywords: documents collections;Hungarian political parties in Slovakia;interwar Czechoslovakia;

For exploring the history of Hungarian parties in Czechoslovakia between the two world wars, it is indispensable to get acquainted with the original sources and documents. After the Second World War, following the measures affecting the Hungarian minority, the archives of these parties were lost or scattered, therefore the search of documents relating to them has been a difficult task for historians. Information on the history of these parties can only be traced out of various domestic and foreign archives and of different types of funds, and by gathering news and reports after reading dozens of contemporary newspapers.In this collection of documents I have included 53 documents on the second strongest party among the Hungarian civic parties in Czechoslovakia between the two world wars: the Provincial Hungarian Smallholder Agrarians’ and Craftsmen’s Party (Hungarian: Országos Magyar Kisgazda Földmíves és Kisiparos Párt), as well as on its successor, the Hungarian National Party (Hungarian: Magyar Nemzeti Párt) established in 1925. This volume is closely linked to my collection of sources published in 2004, entitled Documents on the History of the Provincial Christian Socialist Party 1919–1936 (Hungarian: Dokumentumok az Országos Keresztényszocialista Párt történetéhez 1919–1936), and the book called Interest Protection and Self-organization. Chapters on the History of the Hungarian Political Parties in Czechoslovakia 1918–1938 (Hungarian: Érdekvédelem és önszerveződés. Fejezetek a csehszlovákiai magyar pártpolitika történetéből 1918–1938). The former collection of documents contains sources on the other significant political platform of the period, the Provincial Christian Socialist Party. The present book follows the proven editorial principles of the latter.In the introductory study I briefly summarize the history of the party, present its program and its role in the Hungarian minority politics. I deal more specifically with the party’s election results and the party-related press.While selecting the documents, I sought to publish those introducing the events taking place within the party and the processes going on in domestic politics. The smallholders’ party had not only changed its name over its 16 years of independent operation, but had politicized along various programs and strategies until the summer of 1936 when it merged with the Provincial Christian Socialist Party. In the introductory study, as well as in the comments and notes attached to the documents, I refer to each turning point separately.The documents are presented in a chronological order, marked with Arabic numerals. The serial number is followed by a short regest, which indicates the date and place of origin of the document. In the rest of the regest, the reader is provided with information about the contents of the document without evaluation or classification. I sought to communicate the full text of the sources. Where it was not possible because of the extent of the document or for reasons of substance, I applied partial publication, while indicating the omissions with a square bracket [...]. In case of articles taken over from the press, the text is preceded by the article´s original title. The text of the document is in all cases followed by a mark indicating the location of the document. Then I give the type of the document (clarification, phrasing, copy) and the method of its production (handwritten text, typed, printed text). In case of articles taken over from the press, I refer to the title of the paper, page number, and the author’s name. Each document is followed by a commentary. In some sentences I introduce the document’s author(s), its production and other related documents, as well as the relevant literature.The understanding of the collection’s documents is supported by a wide range of notes and by names register. In addition, the volume is complemented by a rich photographic material aiming to give a well-rounded picture of the era.

More...

Keywords: Czechoslovakia;1989–1990;Hungarian minority;political parts;political elite; voters

The monograph deals with the subject-matter of the political identity of the Hungarian political elite and Hungarian voters in Slovakia in the period from 17 November 1989 to the end of 1990.In the author´s view, political identity is a four-dimensional phenomenon. It consists of a dimension of values, opinions, actions and self-affirmation.In the first chapter, the author analyzes the conditions and background of the emergence of the first post-November Hungarian political elite, i.e. the Hungarian Independent Initiative (MNI), the Együttélés Political Movement and the Hungarian Christian Democratic Movement (MKDH). She deals with their values and ideological profile, views presented in the form of political programs, statements and press appearances, their typology and fault lines.The second chapter describes the ideas of the people of Czechoslovakia, the ethnic Hungarians in Slovakia and the November political elite (Civic Forum (OF), Public Against Violence (VPN) and the Hungarian Independent Initiative) in November 1989 about the future, to what extent their visions corresponded, how the views of the political elite gradually changed and how these departed from the ideas of the majority of citizens.The third chapter discusses in what political actions were the values and views of the political elite manifested, in what fundamental political-economic changes they were translated into and what were the societal impacts of these changes.The central theme of the fourth chapter is the transformation of living conditions and value orientations of the population—especially of citizens living in the Slovakian part of the country—, which part was affected by the consequences of the political elite´s above-mentioned political and economic decisions and their implementation. At the same time, in this chapter we get a picture of how people—both Slovaks and Hungarians—lived through these changes and what they thought about them.The fifth chapter deals with the increasingly pressing national minority issue, which manifested itself in the form of Czech-Slovak and Slovak-Hungarian tensions. The analysis concerns both forms of nationality issues, both from the perspective of the political elite and of the Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian public.In the sixth chapter, the author seeks an answer to the question, what mirror did the citizens hold up to the political elite in the first free parliamentary and municipal elections. Given the election results, how did the political identity of the voters and that of the political elite converge in them?The final, seventh chapter outlines the typology of the political elite´s political identity and that of the voters belonging to the Hungarian national minority from the end of 1989 to the end of 1990.

More...

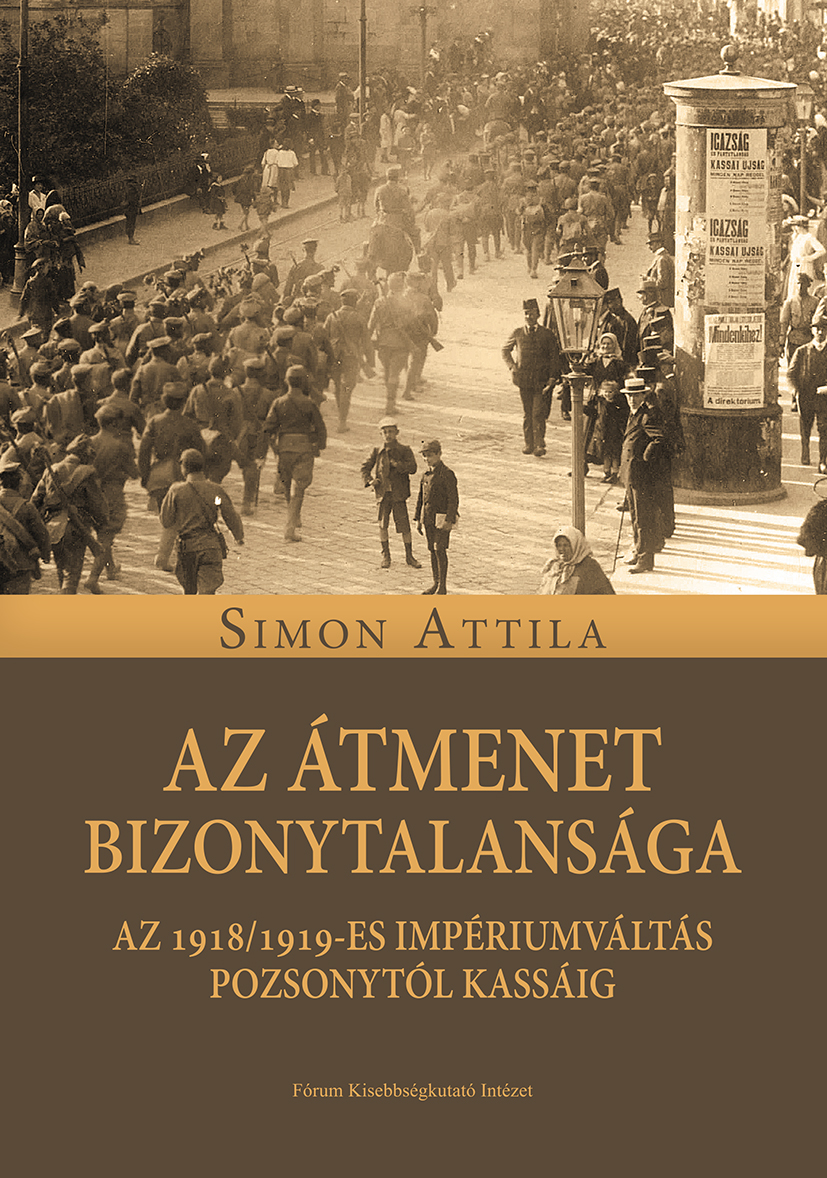

Keywords: Hungarians; the establishment of the Czechoslovak state; 1918/1919; occupation; invaders; local events; individual destinies

The present volume, which aims to show how the 1918/19 transfer of sovereignty taking place in what is now known as southern Slovakia, summarises the author's research on the subject over the previous four to five years. And although the region is inhabited by Hungarians and Slovaks, the book focuses primarily on the aspirations of the Hungarians living there, the reason of which is not only the numerical superiority of the Hungarians, but also the lack of national self-organisation of the Slovaks living there at the time. As Ondrej Ficeri put it in connection with Košice, it was in vain for the Slovaks to make up a large part of the population there if they had not yet been ethnicised and had not yet formed an organised national community that would have made its voice heard and would have tried to assert its will.The choice of perspective, i.e. the fact that I have focused my analysis primarily on the fate of Hungarians living in the region concerned, unavoidably implies that I am talking about Czechoslovak occupation in the book. For the Hungarians of Žitný ostrov or Gemer, the invasion of Czechoslovak troops was clearly an occupation, and this is how they felt in January 1919 and also when the Czechoslovak army occupied their region for the second time after the withdrawal of the Hungarian Red Army. I myself therefore feel justified in using this term.In the book I try to answer questions such as how the inhabitants of the region under study experienced the period of the Aster Revolution, how they reacted on hearing the news of Czechoslovak occupation, how they received the invaders, how their relationship with the new state power developed, and what events took place in the months of the turn in the region of present-day southern Slovakia.The chapters of the book review the events that took place on this territory from the autumn of 1918 to the autumn of 1919. However, the geographical accents are not evenly distributed, as very little is said about the region east of Košice, due to the lack of relevant sources. The main focus of the research was on regions and especially towns for which I had a wealth of archival and press sources at my disposal. I mainly examined Košice, Komárno, Rimavská Sobota, Lučenec, but also Levice, Nové Zámky and Rožňava. On the other hand, I will only touch on Bratislava, as the rich source material on the city would have been beyond the scope of this volume.Just as the volume is not uniform in its territorial accents, neither is it uniform in its thematic emphases. My attention was primarily directed on the interaction between the Hungarian population and the Czechoslovak power, and in this context on the transformation of life in the region under study, but not in a comprehensive way. Culture, the fate of the theatres, education and schools are just some of the topics that I have not examined. This is partly because they have already been dealt with by more qualified researchers in the subject. Nor did I feel motivated or well-prepared to explore the military history aspects of the subject.Little relevant literature has yet been written on the incorporation of present-day southern Slovakia into Czechoslovakia, or on how the towns here experienced the change of sovereignty. This volume therefore draws heavily on new, previously unexplored archival sources.The history of the political turn in southern Slovakia is both a history of disintegration and a history of construction, as the disintegration of the Kingdom of Hungary is accompanied by the construction of the Czechoslovak Republic. Despite this, the Hungarian literature on Trianon, or the Czech and Slovak literature on the formation of Czechoslovakia, almost always analyses only one of the two processes. The result of this cannot be much else than the incompatibility of the 'grand narratives'.However, the volume presented to the reader is primarily dominated by "small stories", local events and individual destinies, which can only be understood if the disintegration and construction are examined together, in their interrelationship. The contemporary history of Komárno or Košice and the people who lived there is at once the history of the withdrawal of the Hungarian state and the history of the establishment of the Czechoslovak state.The occupation of the region by Czechoslovakia was a more complex process than previously thought, in which the course of events was not necessarily determined by the opposition of the two centres of power, Budapest and Prague, but was influenced at least as much by local forces: the leadership of a given city, taking advantage of Budapest's passivity, the commanders of the occupying troops, and the interaction of these actors.Traditionally, the national aspect has been identified as the central organizing principle of the transfer of sovereignty in southern Slovakia, which assigns the place of the individual actors in contemporary events on an ethnic basis. This, however, is the result of a simplification and misunderstanding of the conditions of the time, and leads to erroneous conclusions such as that the Hungarians in Upper Hungary rejected Czechoslovakia, which, moreover, brought them democracy, solely on the basis of nationalism.But this is a misconception, as is the view that at the time of the change of sovereignty, the old, undemocratic Kingdom of Hungary and the new, democratic Czechoslovakia were opposing worlds in terms of their political systems. There are not only national motives in the attitude of the social democratic groups in Bratislava, in Košice and other areas (and even more so in the case of the German and Slovak workers who went on strike with them) towards Czechoslovakia. For the social democrats, the Aster Revolution was a victory for their earlier aspirations and the democratisation of the country, and the developments after the Czechoslovak occupation were perceived as a process against this. For them, as a manifesto of the workers in Košice indicates, the Czechoslovak army was both a representative of an alien national and class (imperialist) power, and this was what made their rejection so fierce.The two elements of the change of sovereignty in Upper Hungary, the disintegration of the Hungarian state and the establishment of the Czechoslovak state, were an overlapping process. From 29 December 1918, when the Czechoslovak troops occupied Košice, the Czechoslovak state power was already present in the city, but the Hungarian state was also there: its institutions were there, its laws were in force and, above all, its representatives were there. Although the city already belonged to Czechoslovakia, in January 1919 the Czechoslovak presence was stronger in only one segment of the state power: the army. In everything else (institutions, legislation, administration), the Hungarian state seems to be more dominant. And even if its influence is gradually diminishing, while the Czechoslovak presence is gradually growing stronger, it is still present. If this had not been the case, the arrival of the Red Army of the Hungarian Soviet Republic could not have restored the 'Hungarian world' so quickly. The change only accelerates after the second "Czechoslovak occupation", when not only the institutional and administrative takeover is completed, but also the population's acceptance of Prague's power increases.For the above reasons, I believe that one of the most important messages of this volume is to emphasise the phenomenon of transience, even though this concept is not a well-established element in our historiography. However, even if we ignore it, transience is a phenomenon that exists, a phenomenon that marks the in-between periods when the usual order of society ceases to function, or functions only partially, because of some kind of rupture, while a new order is already in the process of being formed. From the point of view of the region examined in this volume, i.e. southern Slovakia, the period of almost a year from autumn 1918 to autumn 1919, during which the role of historical Hungary was taken over by the Czechoslovak state, can rightly be regarded as such a period. The months of transition.The feeling of transience was strongly linked to another feeling, that of uncertainty. For the citizen of southern Slovakia, it was not the fact of change per se that was frightening, but rather the uncertainty that went with transience. The unpredictability of the future. The approach of the Czechoslovak army was also a source of fear, primarily because they did not know what it would bring and what it would entail. And the final demarcation of the borders and the second occupation was a step towards consolidation because it put an end to uncertainty.From this point of view, the gradual abandonment of the rejection of the Czechoslovak state by the Hungarians of southern Slovakia and their pragmatic acceptance was also the result of a desire for certainty and stability that could replace uncertainty. From the summer of 1914 onwards, this was perhaps what they lacked most of all. It is a curious twist of history that it was Czechoslovakia, not Hungary, that gave them stability. Then and there it seemed to be enough to reconcile them to their fate in the long term. It did not take long, however, for it to become clear that this was not enough, that the Hungarians, from Bratislava to Košice, expected more.

More...

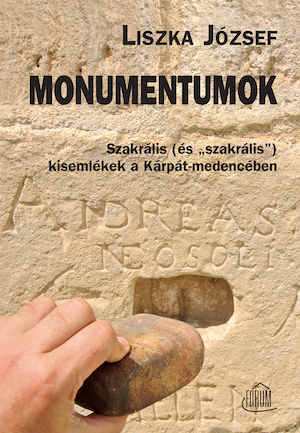

Keywords: small sacral relics;saints; faith of statues; cross; crucifix; Lourdes cave; calvary; column with sacral motives; definition; categorisation;terminology;

The scientific study (documentation, analysis, interpretation) of small outdoor sacral relics (pictures placed on trees, columns with sacral pictures, roadside crucifixes, statues of saints, etc.) has a history of only a few decades, both in the Hungarian linguistic area and among neighbouring peoples. The first third of this publication is devoted to a terminological and typological classification of the extremely diverse material, followed by a thematic presentation of the material from the viewpoint of ethnology of religion and cultural history. The next section discusses the motives, historical and geographical aspects of the erection of small sacral relics. The strength of the volume is the bibliography, which exceeds 100 pages and can be regarded as a selected bibliography of the subject in terms of the Carpathian Basin, in addition to the (specialized) literature cited in the book. The publication is rounded off with almost half a thousand photographs—some of which are in colour—, drawings and maps, and the geographical, personal name and subject indexes make it easy to use.

More...

Keywords: ethnology; cultural history; Central Europe; Hungarian, Slovak and German ethnographers; nations; fairy tale; religion; folklore; folklorism

The pieces in this volume are real experiments, since they attempt to interpret a scientific work or book, to outline the work or career of a colleague, to formulate a scientific and/or public problem in a sharp but preferably not offensive way, and yes, they can also be a condensation attempt to outline and summarize one's own scientific ars poetica. The genres of this condensation attempt are reviews, critiques, peer reviews, discussion papers, newspaper columns, diary entries, study pieces, book reviews of study value, tributes and obituaries, in short, this volume is truly a collection of gentlemanly mischief. What binds them together, apart from the author himself, is the broad framework of ethnography, folklore and cultural history, European ethnology and museology, dialectology and religious ethnography, and the vast virtual professional and friendly circle of their practitioners.

More...

Keywords: Hungarians; the establishment of the Czechoslovak state; 1918/1919; occupation; invaders; local events; individual destinies

The present volume, which aims to show how the 1918/19 transfer of sovereignty taking place in what is now known as southern Slovakia, summarises the author's research on the subject over the previous four to five years. And although the region is inhabited by Hungarians and Slovaks, the book focuses primarily on the aspirations of the Hungarians living there, the reason of which is not only the numerical superiority of the Hungarians, but also the lack of national self-organisation of the Slovaks living there at the time. As Ondrej Ficeri put it in connection with Košice, it was in vain for the Slovaks to make up a large part of the population there if they had not yet been ethnicised and had not yet formed an organised national community that would have made its voice heard and would have tried to assert its will.The choice of perspective, i.e. the fact that I have focused my analysis primarily on the fate of Hungarians living in the region concerned, unavoidably implies that I am talking about Czechoslovak occupation in the book. For the Hungarians of Žitný ostrov or Gemer, the invasion of Czechoslovak troops was clearly an occupation, and this is how they felt in January 1919 and also when the Czechoslovak army occupied their region for the second time after the withdrawal of the Hungarian Red Army. I myself therefore feel justified in using this term.In the book I try to answer questions such as how the inhabitants of the region under study experienced the period of the Aster Revolution, how they reacted on hearing the news of Czechoslovak occupation, how they received the invaders, how their relationship with the new state power developed, and what events took place in the months of the turn in the region of present-day southern Slovakia.The chapters of the book review the events that took place on this territory from the autumn of 1918 to the autumn of 1919. However, the geographical accents are not evenly distributed, as very little is said about the region east of Košice, due to the lack of relevant sources. The main focus of the research was on regions and especially towns for which I had a wealth of archival and press sources at my disposal. I mainly examined Košice, Komárno, Rimavská Sobota, Lučenec, but also Levice, Nové Zámky and Rožňava. On the other hand, I will only touch on Bratislava, as the rich source material on the city would have been beyond the scope of this volume.Just as the volume is not uniform in its territorial accents, neither is it uniform in its thematic emphases. My attention was primarily directed on the interaction between the Hungarian population and the Czechoslovak power, and in this context on the transformation of life in the region under study, but not in a comprehensive way. Culture, the fate of the theatres, education and schools are just some of the topics that I have not examined. This is partly because they have already been dealt with by more qualified researchers in the subject. Nor did I feel motivated or well-prepared to explore the military history aspects of the subject. Little relevant literature has yet been written on the incorporation of present-day southern Slovakia into Czechoslovakia, or on how the towns here experienced the change of sovereignty. This volume therefore draws heavily on new, previously unexplored archival sources. The history of the political turn in southern Slovakia is both a history of disintegration and a history of construction, as the disintegration of the Kingdom of Hungary is accompanied by the construction of the Czechoslovak Republic. Despite this, the Hungarian literature on Trianon, or the Czech and Slovak literature on the formation of Czechoslovakia, almost always analyses only one of the two processes. The result of this cannot be much else than the incompatibility of the 'grand narratives'. However, the volume presented to the reader is primarily dominated by "small stories", local events and individual destinies, which can only be understood if the disintegration and construction are examined together, in their interrelationship. The contemporary history of Komárno or Košice and the people who lived there is at once the history of the withdrawal of the Hungarian state and the history of the establishment of the Czechoslovak state.The occupation of the region by Czechoslovakia was a more complex process than previously thought, in which the course of events was not necessarily determined by the opposition of the two centres of power, Budapest and Prague, but was influenced at least as much by local forces: the leadership of a given city, taking advantage of Budapest's passivity, the commanders of the occupying troops, and the interaction of these actors.Traditionally, the national aspect has been identified as the central organizing principle of the transfer of sovereignty in southern Slovakia, which assigns the place of the individual actors in contemporary events on an ethnic basis. This, however, is the result of a simplification and misunderstanding of the conditions of the time, and leads to erroneous conclusions such as that the Hungarians in Upper Hungary rejected Czechoslovakia, which, moreover, brought them democracy, solely on the basis of nationalism.But this is a misconception, as is the view that at the time of the change of sovereignty, the old, undemocratic Kingdom of Hungary and the new, democratic Czechoslovakia were opposing worlds in terms of their political systems. There are not only national motives in the attitude of the social democratic groups in Bratislava, in Košice and other areas (and even more so in the case of the German and Slovak workers who went on strike with them) towards Czechoslovakia. For the social democrats, the Aster Revolution was a victory for their earlier aspirations and the democratisation of the country, and the developments after the Czechoslovak occupation were perceived as a process against this. For them, as a manifesto of the workers in Košice indicates, the Czechoslovak army was both a representative of an alien national and class (imperialist) power, and this was what made their rejection so fierce.The two elements of the change of sovereignty in Upper Hungary, the disintegration of the Hungarian state and the establishment of the Czechoslovak state, were an overlapping process. From 29 December 1918, when the Czechoslovak troops occupied Košice, the Czechoslovak state power was already present in the city, but the Hungarian state was also there: its institutions were there, its laws were in force and, above all, its representatives were there. Although the city already belonged to Czechoslovakia, in January 1919 the Czechoslovak presence was stronger in only one segment of the state power: the army. In everything else (institutions, legislation, administration), the Hungarian state seems to be more dominant. And even if its influence is gradually diminishing, while the Czechoslovak presence is gradually growing stronger, it is still present. If this had not been the case, the arrival of the Red Army of the Hungarian Soviet Republic could not have restored the 'Hungarian world' so quickly. The change only accelerates after the second "Czechoslovak occupation", when not only the institutional and administrative takeover is completed, but also the population's acceptance of Prague's power increases.For the above reasons, I believe that one of the most important messages of this volume is to emphasise the phenomenon of transience, even though this concept is not a well-established element in our historiography. However, even if we ignore it, transience is a phenomenon that exists, a phenomenon that marks the in-between periods when the usual order of society ceases to function, or functions only partially, because of some kind of rupture, while a new order is already in the process of being formed. From the point of view of the region examined in this volume, i.e. southern Slovakia, the period of almost a year from autumn 1918 to autumn 1919, during which the role of historical Hungary was taken over by the Czechoslovak state, can rightly be regarded as such a period. The months of transition.The feeling of transience was strongly linked to another feeling, that of uncertainty. For the citizen of southern Slovakia, it was not the fact of change per se that was frightening, but rather the uncertainty that went with transience. The unpredictability of the future. The approach of the Czechoslovak army was also a source of fear, primarily because they did not know what it would bring and what it would entail. And the final demarcation of the borders and the second occupation was a step towards consolidation because it put an end to uncertainty.From this point of view, the gradual abandonment of the rejection of the Czechoslovak state by the Hungarians of southern Slovakia and their pragmatic acceptance was also the result of a desire for certainty and stability that could replace uncertainty. From the summer of 1914 onwards, this was perhaps what they lacked most of all. It is a curious twist of history that it was Czechoslovakia, not Hungary, that gave them stability. Then and there it seemed to be enough to reconcile them to their fate in the long term. It did not take long, however, for it to become clear that this was not enough, that the Hungarians, from Bratislava to Košice, expected more.

More...

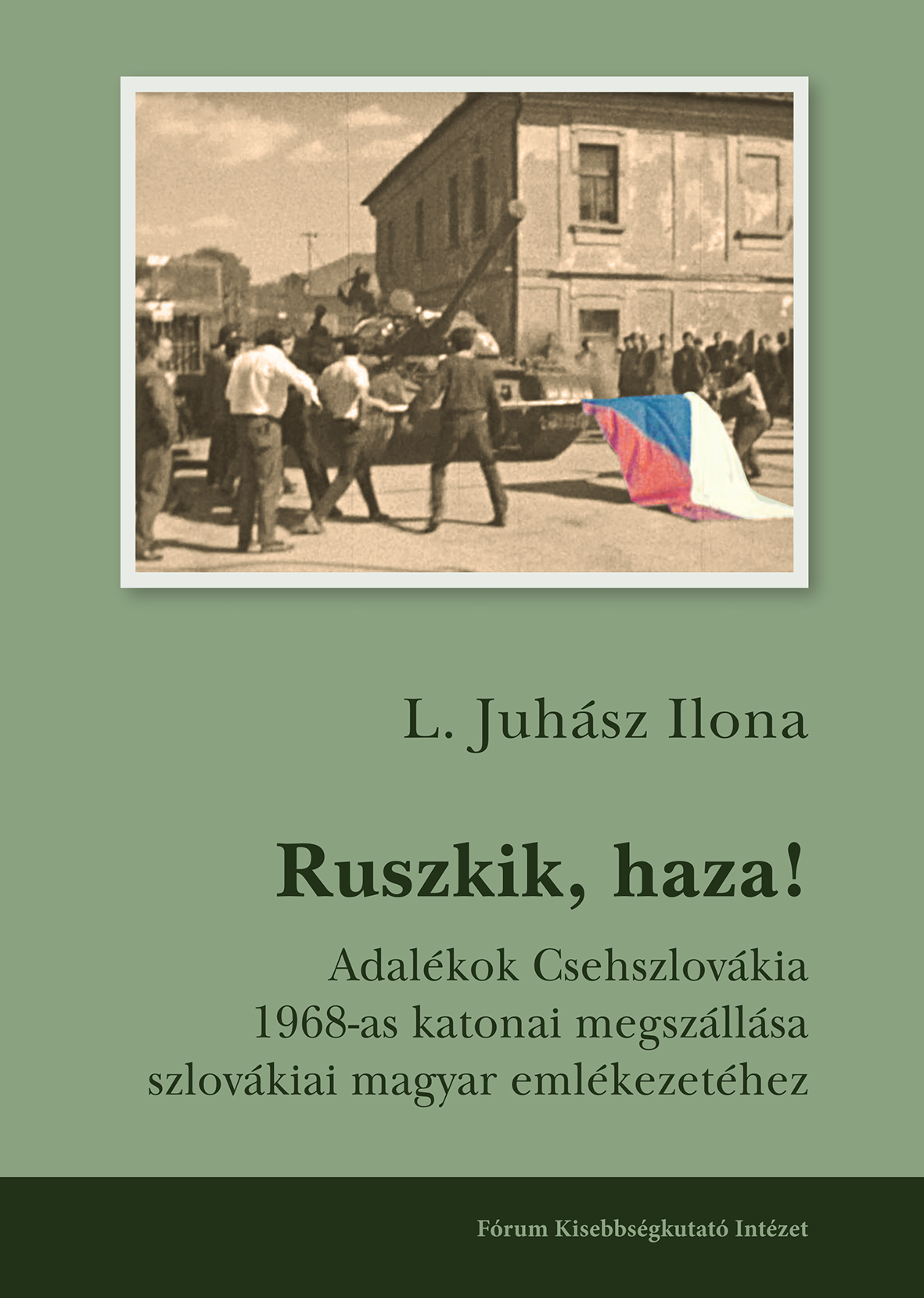

Keywords: local memory; oral history; 1968; Soviet occupation; Slovakia; Hungarian minority

This book summarises the results of a research undertaken by the Centre for Ethnology of the Forum Minority Research Institute in Komárno. The research work assisted by external collaborators, was carried out in selected Hungarian-populated municipalities in Southern Slovakia. The research was not designed to exactly reconstruct the events of the 1968 invasion, but to examine what local memory has preserved at the micro level about the Soviet occupation. How did the informants experience the events of that time as eyewitnesses, and what memory have people born later kept of the stories they heard from their parents or others. With a few exceptions, no hostile comments were made about the invading Soviet army. In general, it can be said that many of them relieved the Soviet soldiers of responsibility because, in their opinion, they had followed orders and could do nothing against it, they had to come here. Informants viewed in positive terms that the Soviet soldiers helped unified agricultural cooperatives with agricultural work and in other areas as well, and last but not least, “we could bargain with them,” they had cheap access to fuel, various technical items etc. In summary, the vast majority of informants do not see the 1968 invasion as a tragic event, they are much more preoccupied with today’s real problems (or those considered real due to media influence) such as migration or unemployment. Many feel somewhat nostalgic about the period following 1968 when life was better, and they claim they were not bothered by the Soviets. The memory of informants has been influenced by many things over time, especially newspapers, television, and radio, which may have significantly influenced and modified personal stories over the past decades.

More...

Keywords: Hungarian minority; Czechoslovakia/Slovakia; elections; censuses; Hungarian parties; Hungarian schools; Hungarians in Slovak schools

The book was written and is being published at a time when Hungarian politics in Slovakia is, in the opinion of many, at a crossroads. The authors of Under the Influence of Necessity do not hide their (sometimes controversial) views on the current situation and possible ways out, but the result of their work, organized in a book, is not a political pamphlet. The assessment of the crisis and the proposal for a way out are not based on superficial impressions, but on a wealth of figures, which the authors have painstakingly compiled and organized over many years. Thanks to these data, the interested reader can turn the pages of this volume even if he or she does not share the authors' conclusions. The reader will be able to get a comprehensive picture of the census and school statistics of the Hungarian minority in (Czecho)Slovakia, which now goes back more than a hundred years. For those interested in the profession and minority politics, the main contribution of the volume lies in the more detailed and newly processed data series than previous research, which provide a plastic picture of the parliamentary, European and regional elections from 1920 to the present, as well as the performance of parties that can be defined as Hungarian and the composition of their electoral base.

More...

Keywords: women’s life; Slovakia; Hungary; socialism; family; nutrition; clothing; cleanliness; hygiene; celebrations; holidays; 1955–1989

The two authors ask whether it is possible to generalise the picture of socialist Slovakia and Hungary in terms of women's lives. Their answer is that, despite the cultural proximity and affinity, this cannot be done at all. After all, that is not their aim either. Rather, it is an attempt to find the subtle differences, the apparent trifles of everyday and festive life, even assuming that they offer a fragmentary picture. The period from the mid-fifties to the time of the regime change is here interpreted through their own vision, life experiences and experiences. It is important for ethnologists to show cultural changes and processes. In a harmonious unity of selected images and texts, they describe life's circumstances of the girls and women.

More...

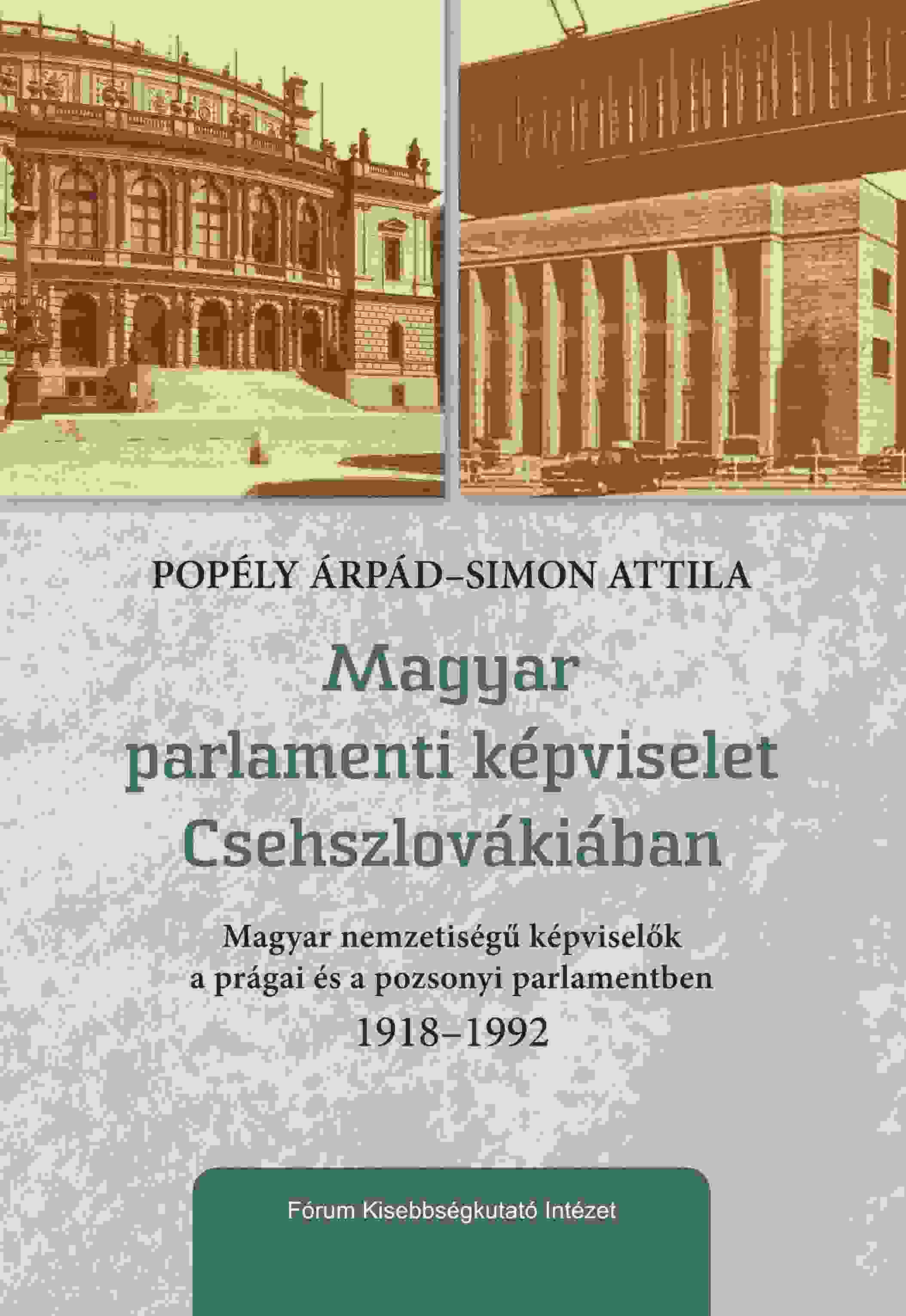

Keywords: Czechoslovakia; 1918–1992; parliaments; Hungarian parliamentarians; deputies and senators

The Hungarian community in Slovakia, like its representation in parliament, has a history of more than a century. However, with the exception of a few recently published partial monographs, there has been no scholarly work on Hungarian parliamentary representation in the former Czechoslovakia. The present volume is the first attempt to summarize the history of parliamentary representation of the Hungarian minority in former Czechoslovakia from the country's formation in 1918 until its dissolution in 1992, as well as the biographies and political careers of its ethnic Hungarian parliamentarians and senators. This volume is also a pioneering undertaking in that no similar publication has yet been compiled on Czech and Slovak members of the Prague and Bratislava parliaments either. Since post-World War II Slovakia had its own legislative body, the Slovak National Council, the book naturally deals not only with the parliaments of Prague, the National Assembly and the Federal Assembly, but also with the Bratislava parliament and its Hungarian representatives. The fact that Prague had a bicameral parliament already during the First Republic and after the federal transformation of the country further increased the number of deputies covered in the book. In addition, between the two world wars, Subcarpathian Rus (today Carpatho-Ukraine) was also part of the Czechoslovak state, and ethnic Hungarian deputies and senators from there were elected to the National Assembly in Prague. Obviously, they were among the Hungarian legislators in Czechoslovakia, so it is only natural that they have been included in this volume, which thus presents a total of 246 Hungarian members and senators of the Prague and Bratislava parliaments. Of these, 45 were deputies and senators of the First Republic, 134 were deputies and senators in the years of the one-party state, 65 were deputies and senators of post-communist Czechoslovakia, and two were deputies and senators of both the single-party state and the parliaments after its collapse.In line with the generally accepted chronology of Czechoslovak history, the volume is divided into three major chapters. The first chapter covers the period of the First Republic, the second the years of the single-party system, and the third the period from the removal of the totalitarian communist regime to the end of the (federal) state. Only the post-World War II coalition period, which was a period of disenfranchisement for the Hungarian minority, is not included as a separate chapter, as the Hungarian population was deprived of the right to vote and thus to be represented in parliament. Nor does the volume deal with the period of the Slovak state during the Second World War and the parliamentary activities of its only Hungarian MP, János Esterházy, since the Slovak state parliament—unlike the post-war Slovak National Council—did not operate within the Czechoslovak state. Each chapter begins with a study of the political background and Hungarian parliamentary representation of the period, followed by a presentation of the ethnic Hungarian legislators of the period.The entries summarising the political and biographical background of each MEP include biographical details of the MEP, the number of the election term in which he or she was elected, the legislature of which he or she was a member or senator, the period of his or her mandate, the constituency in which he or she was elected and the party for which he or she was elected. The beginning and end of a mandate are often linked to different events in different registers or databases and are therefore given in different ways. The present volume considers the beginning of a mandate as the date of taking the oath of office and the end as the date of the next elections, except, of course, in cases where a person has been recalled, resigned, or died before the end of his mandate.The most important sources of biographical data on the MPs were their personal papers and the cadre reviews prepared on them. The personal papers of the MPs and senators in Prague are kept in the Archives of the Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic, while those of the MPs in Bratislava are kept partly in the Archives of the National Council of the Slovak Republic and partly in the Slovak National Archives. The cadres' reviews from the single-party state years are kept in the Communist Party´s fonds in the National Archives of the Czech Republic and the Slovak National Archives. Although in some cases their contents had to be corrected, the primary source of information on the ethnicity of MPs was the handbooks issued for each elected parliament, including, among others, the data of the MPs. The work of Members of Parliament has been possible to reconstruct from the press of the time and the stenographic records of parliamentary sittings. At the end of the volume, there is a reference list and bibliography, and an index of the names of persons and places appearing in the book.

More...