Wystawy sztuki polskiej we Francji w latach 1921-1939

Exhibitions of Polish Art in France in 1921-39

Author(s): Anna WierzbickaSubject(s): Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Visual Arts, History of Art

Published by: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk

Keywords: Exhibitions of Polish Art in France in 1921-39; Polish art 20th century;

Summary/Abstract: Exhibitions of Polish Art in France in 1921-39 The exhibition of Polish art held in 1921 by the Salon de la Société nationale des beaux arts was the first after the Great War presenting the accomplishments of artists from Poland. Prepared by the Polish government, or, to be more precise, by the Bureau of Foreign Propaganda of the Board of the Council of Ministers, under the auspices of the politicians: Józef Piłsudski and France’s President Alexandre Millerand, two months after signing the political treaty between France and Poland, it was meant to draw public attention to Poland and its culture. While the earlier displays held by the Polish colony in France had presented merely works of the artists that represented the colony, this one also included pieces by leading painters and sculptors active in Poland from the late 18th up to the 20th century. The organizers (the sculptor Edward Wittig and the painter Ferdynand Ruszczyc), meant first of all to represent Polish art, its best most characteristic works enhancing the ‘Polish character’ of the artistic output in Poland. However, contrary to the intentions, French commentators pointed out mainly to the dependence of Polish art on French art. The exhibition yielded negative reviews, similarly as that of ‘Young Poland’ at the Musée Crillon in 1922 (displaying, first of all, the Formists) and that of the Polish section at the Salon d’Automne in 1928 (this presenting artists from Poland, firstly members of the ‘Praesens’ Group), and in the painting section representatives of various groups, of different age, mainly the ‘Rhythm’ Group (Borowski, Malczewski, Niesiołowski, Pruszkowski, Skoczylas, Stryjeńska, Wąsowicz). The display was organized in cooperation between the Association of Polish Artists established in France and the Polish Society of Literary and Artistic Exchange between France and Poland (Société polonaise d’échanges littéraires et artistiques entre la France et la Pologne), presided by Mieczysław Treter, and forming the Paris branch of the Society of Promoting Polish Art among Foreigners (TOSSPO) set up a year earlier, and operating under the patronage of the Ministry of Religious Beliefs and Public Enlightenment as well as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. All the three displays, prepared hurriedly, chaotically, and under difficult circumstances, were badly synchronized in time. They did not take into account the cultural policy of the beholders and their preferences. Held at the time when ‘the return to order’ had become a dominant slogan in Paris, while landscapes, portraits, and genre scenes dominated in the French artists’ output, they proved to be a failure. At the time TOSSPO, organizer of the majority of exhibitions abroad, had openly started to favour works of the artists drawing inspiration from folk art, whose oeuvre was considered to display the affirmation of Polishness and the continuity of national forms. The Society’s most frequently organized exhibitions included displays of carpets and tapestries designed by e.g. Józef Czajkowski, Edward Trojanowski, and Wanda Kossecka, or woodcuts by Edmund Bartłomiejczyk, Bogna Krasnodębska, Stefan Mrożewski, and Władysław Skoczylas. The Polish section was, for example, successful at the Third European Woodcut Exhibition (La troisième Exposition de La Gravure sur Bois originale en Europe) held by L’Union Centrale des Arts décoratifs and the Société de la gravure sur bois originale in 1928. A year earlier works by Józef Czajkowski, Wojciech Jastrzębowski, and Edward Trojanowski (representing the Polish Applied Art Society) and 40 works by the artist of the ŁAD Artists’ Cooperative had been shown as part of the Polish section organized by TOSSPO and the Society of Artistic and Literary Exchange between France and Poland at the first international Exhibition of Carpets of North and Eastern Europe (Le Tapis. Première exposition. Europe Septentrionale et Orientale) held at the Musée des arts décoratifs, Pavillon Marsan, in 1927. Good relations between Poland and France did not last long. Already in the early 1920s, the collapse of the strong-arm policy that France had implemented towards Germany was visible, and so was the attempt of the West to reach a consensus with Berlin. The late 1920s also coincided with the beginning of the Great Depression following Black Tuesday in 1929. In order to warm up Poland’s image in France and in an attempt to draw the attention of the French people to our country, with their politicians being favourable to Germany, an exhibition at the Jeu de Paume was held. Launched on 22 December 1930, the display titled La Pologne 1830–1920–1930 was a major event, mainly of political impact. Antoni Potocki, responsible for selecting art pieces from France, was the exhibition’s instigator and organizer, while Mieczysław Treter served as the organizer responsible for choosing works from the Second Polish Republic. The propaganda goal was unambiguous: the organizers’ aim was to create a totally novel image of Poland, to replace the concept of ‘noble yet unfortunate Poland’(noble et malheureuse Pologne), with the image of a powerful country, Poland defending the West against the ‘Eastern onslaught’. It therefore synthesized the history of Poland previously unknown in France, until then thought to have been associated primarily with Sobieski, Mickiewicz, and Chopin. Focusing on three major dates: 1839, 1829, and 1930, it was meant to show respective developments in Poland’s history in a way that would enhance Poles’ contribution to defending the West, and therefore Christianity as well as the Latin character of Europe. And this exhibition was actually successful. Having been organized at the right time, at a prestigious venue, and widely advertised in the press, it turned out to be one of the few displays that received an enthusiastic welcome. The 1930 exhibition, also propaganda-wise, was completed with two subsequent ones mounted respectively in 1933: Sobieski, King of Poland, in Engravings from the Period (‘Sobieski roi de Pologne d’après les estampes de l’époque’) and in 1935 (then the Polish Room included documents, letters, armours, uniforms, paintings, and prints from the period related to Poles in the French army in the 17th and 18th centuries) held for the purpose of the exhibition Two Centuries of Military Glory 1610-1814 (Deux Siècles de Gloire Militaire 1610–1814) at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Pavillon de Marsan, with the contribution of the Polish Library. All the three: from 1930, 1933, and 1935 respectively, harmonized with Poland’s major diplomatic endeavours, with all the works having been selected topically and in accordance with the suggested interpretation. All were also made events of a political impact. They represented, however, but a swan song in view of the events that were to follow. The task of the Polish Section at the 1937 Exhibition Art and Technology in Modern Life was to present Poland as a strong, modern country, pertaining to the Latin tradition. Similarly as in the course of the earlier exhibitions in 1930-35, Poland’s European character was emphasized, and that of its people who were related to Latin culture and immersed in the Western Christian world. Meanwhile, TOSSPO continued focused on promoting the myth of Slavic Poland. Polish woodcuts and Polish folk art remained our major export commodity until the outbreak of WW II. Still in 1938, a committee at the folk art section was established at TOSSPO, while in the 1930s such Polish exhibitions on the topic still dominated in France; they were held by the Les Amis de la Pologne Society which developed its activity at the time. Moreover, in the 1930s, France was being toured by Polish exhibitions of graphic art, which, in their majority, presented works by the same artists. The displays of Polish graphic art and Polish folk art, organized by TOSSPO beginning as of the mid-1920s, namely from the International Exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Arts, until 1939 were systematically very popular. They perfectly fitted in the period when what was national, what signified the distinctness of a country, was particularly appreciated in France. France perceived Poland, and wanted to see it as a non-Western, Slav-culture country. Interestingly, graphic art was the domain in which Poles won the highest success in the interwar period, not only in France, but also in other European countries and the United States, where the works by, e.g. Edmund Bartłomiejczyk, Tadeusz Cieślewski Junior, Stanisław Ostoja-Chrostowski, Janina Konarska, Bogna Krasnodębska, Stefan Mrożewski, and Władysław Skoczylas were particularly appreciated. Appreciated was not only high-quality craftsmanship, but also the style that, similarly as in France, was called ‘Slavic Style’ by reviewers. In the US, the displays of folk art as well as those of fabrics and tapestries of ŁAD met with warm welcome. In the eyes of average Americans the works fitted their stereotype image of Polish art, essentially of folk character, and so did religious and historical scenes. It was similar in France where in the 1920s tradition and realism were favoured.

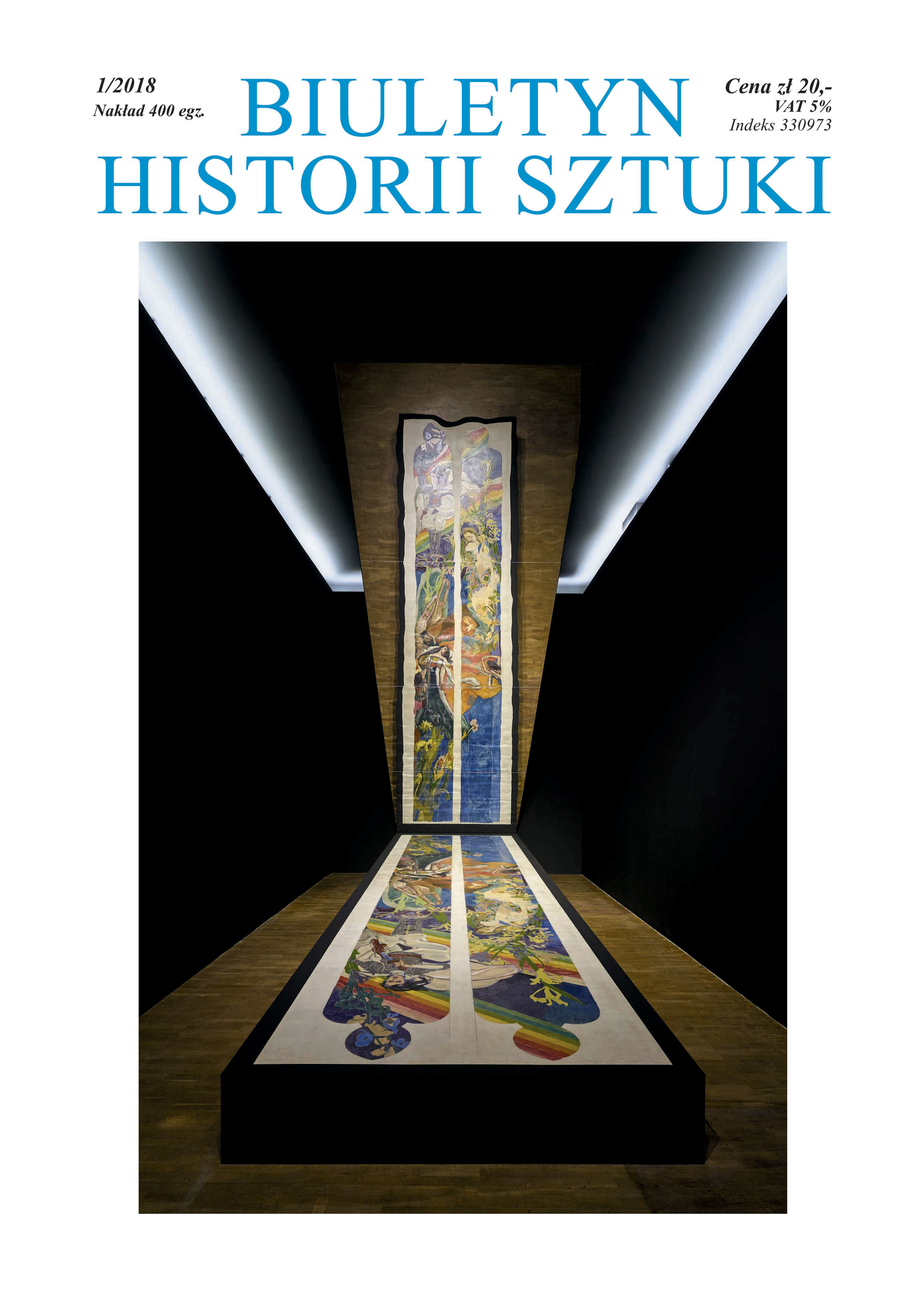

Journal: Biuletyn Historii Sztuki

- Issue Year: 80/2018

- Issue No: 1

- Page Range: 131-178

- Page Count: 48

- Language: Polish

- Content File-PDF