ЈНА на искушењима 60-их година прошлог века

The Yugoslav People’s Army’s Ordeals in 1960s

Author(s): Mile Bjelajac

Subject(s): Military history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), History of Communism

Published by: Institut za noviju istoriju Srbije

Summary/Abstract: The situation in which the Yugoslav People’s Army (YPA) found itself at the time of the events in Czechoslovakia in 1968 was the consequence of turbulences which had previously been rocking the political leadership, the Communist Party and the Army itself. Life outside of the Army was marked

by the economic reform in two phases (1958 and 1965), crisis in the relations between the Yugoslav republics, malfunctioning of political bodies and federal institutions, as was noted on the secret session in March 1962, as well as by Tito’s inconsistency in domestic and foreign policies, further dismantling of the central authority and strengthening of the power of the republics, i.e. of etatism of the

republics, all of which affected discussions about the defence concept. The Brioni Plenum in 1966, student demonstrations in 1968, demonstrations and violence of Albanians in Kosovo and Macedonia in 1968, rise of nationalism in Slovenia and Croatia only served to make the situation in which the YPA found itself, more difficult.

Within the Army itself, after the one-sided cessation of the US military aid program (1958), the new doctrine was introduced – Strategy of Total People’s War, coupled with the changes in formation, that would continuously be upgraded. Although the new doctrine foresaw the combination of frontal and guerrilla warfare, the conflicts insured as to its details. There was a pressure that as much rights and duties in the defence system be allotted to the republics. A group of generals demanded that „self-management” be also introduced in the YPA. Tito, who was the supreme authority in Army matters, didn’t want to give up the unity and to allow anyone to interfere with his leadership. Because of that he had confl icts with the highest Party and political leaders. However, he too was inconsequential when it came to the highest cadres. Because of his resistance to deposition of Ranković, Tito dropped Gošnjak and replaced him with a new minister (1967). All that was coupled with smaller or larger purges of the generals’ corps (only in 1968, 38 generals and 2.400 officers were relieved of their posts). Tito was also the initiator of the new rapprochement and full cooperation with the USSR and the Warsaw Pact (natural hinterland). All modern and heavy weapons started to be obtained from that side, from 1961 onwards. The assessment of the Berlin and Cuban crisis, and particularly the crisis in the Mediterranean and the war in the Middle-East in 1967 certainly contributed to such approach. The Soviets and the Yugoslavs found themselves on the same side then, supporting Arab nations. Tito judged that the main potential threat to Yugoslavia was – the West.

During 1960s it became obvious that the YPA, its partisan elite, started to be eroded by nationalism. This caused anxiety with the pro-Yugoslav cadre. This conflict would remain a staple characteristic of this army until its demise in 1992.

The consequences of the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact were manifold for the YPA, but also for the country as a whole. Strictly militarily and strategically, all further assessments would recon with the possibility of attack from any side, and war-plans and other measures would be adjusted accordingly. Technical modernization of the Army and further development of the military- -industrial complex gained priority. Having analyzed shortcomings of mobilization activities, comprehensive measures were undertaken in order to improve the situation. The Air-Force and Anti-Aircraft Defence, apart from strengthening capacities for defence from the ground, realized a system of underground airfields and shelters must be adopted, as well as putting the whole territory under radar control.

After the political critique of the Army in autumn 1968, it was speedily decided that Central Committees of the republics take defence affairs into their own hands, that general-staffs in the republics be activated, that military staffs were to be founded in municipalities, as well as units and battalions armed with light modern weapons, to secure the communication system and to determine precisely the role of radio and smaller radio stations in case of war. It was believed, with all these measures, the technocratic organization of the Army could be overcome. A new Bill on National Defence was railroaded through the Parliament. Thisopened permanently the question of sovereign command competence and use of the armed forces in Yugoslavia. During the constitutional changes (1969-1974) the wish of some republics was perceptible to gain as much rights in the defence sphere and in managing of the Territorial Defence.

The assessment of the student demonstrations in 1968 wasn’t unanimous within the then military top brass. To be precise, it was radically diverging. The question if a socialist army may intervene in internal political situation was raised then. Tito wanted the Army to concentrate on watching the borders and not doing anything without his explicit approval. However, the events in Kosovo and Macedonia (1968) with demonstrations and elements of rebellion of the Albanians, as well as the escalation of the „Mass Movement” in Croatia, soon convinced also the professed „liberals” among generals that the Army must react in certain situations when public order and the unity of the country are endangered.

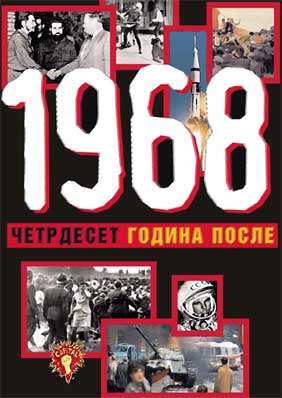

Book: 1968 - четрдесет година после

- Page Range: 379-417

- Page Count: 39

- Publication Year: 2008

- Language: Serbian

- Content File-PDF