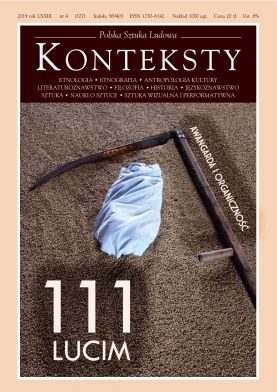

Trzecia droga

Third Way

Author(s): Witold ChmielewskiSubject(s): Fine Arts / Performing Arts

Published by: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk

Keywords: Lucim;art;

Summary/Abstract: Present-day rural culture is no longer the “Kolbergian”, nineteenth-century version. This is not to say, however, that its certain specificity is not alive. Culture from the end of the 1980s is composed of remnants of tradition as well as much that is new and comes from the outside. Upon numerous occasions we are dealing with a degeneration of the customs of old, a process that we just as frequently find terrifying, but this is precisely what the culture of the present-day village looks like. Without doubt, the residents of Lucim have been growing increasingly prosperous – a process accompanied by a decline and deterioration of local culture. Identification with one’s village and even family is declining. Life in a community and family life are noticeably succumbing to descralisation. Numerous festivities and customs linked with work on the land and life on a family farm are either vanishing or growing increasingly insignificant. Nevertheless, Polish folk culture, albeit impoverished, remains sacral. This is the sort of reality we encountered in 1977. Have we managed to change much? Lucim has awakened from its sluggish existence. Increasingly often we came across, and impatiently awaited further such meetings and events. Open proof of this arousal assumed the form of the Lucim Community Centre, at present being constructed by the entire village. Today, Lucim, so recently underappreciated by its residents, who sometimes even declared: “It would be best if Lucim was to be ploughed over”, is becoming a source of pride. First, however, we were compelled to stir the village, to extract it from its lethargic state, and then slowly and tenaciously to awaken and set free its vigour. At the time, Lucim was simply unable to achieve such a target on its own. An outsider had to appear and take on this role. Originally, we acted in the dark, more concerned with being an artist (as was the case at the time of “Akcja Lucim” in 1978) than a co-author of the new Lucim culture. 12 years spent working in Lucim was a period of numerous splendid experiences and much satisfaction, but also of just as many bitter failures and moments of weakness. In time, however, we gained more and more allies, and several years later – also devoted friends. Today, we outright miss each other. Creating, activity, motion, observation, anticipation, studying, testing, modification, resignation, renewal, convincing, improving, crisis and restoration of faith – those are the features of our activity. It is impossible to separate all those elements because they generate a cohesive and multi-dimensional structure. Furthermore, everything takes place within the living organism of the village, and with the participation of its inhabitants. Processes initiated by us in Lucim – not only artistic but also distinctly culture-creating and social ones – started to encompass the entire village. Slowly, there emerged a new local culture combining old traditions and contemporaneity: elements of mass culture and our proposals. Initiatives and works created by the population of Lucim came into being. This was already the onset of “new folk art” – alive, born in the village, and, as in the case of grafting trees, increasingly turning into a part of its tissue, and thus becoming a new and different form of the village’s existence. New folk art serves directly those who co-create it and remains amongst them. By developing and existing predominantly within the people it makes it possible for them to discover and define their identity and self-esteem. Just like regional folk culture of old it is also an alternative vis-à-vis every sort of official culture – in our case, the unified mass culture imposed by the state. At the same time, however, it is an alternative in relation to official Church culture. The village culture of Lucim decisively opposes the depressing vision of the “global village” proposed by McLuhan and remains manifestly local. Simultaneously, it is also universal. In 1984 the process of becoming aware of those truths inspired me to formulate the idea of “post culture” based on the experiences of social art and “new folk art”. Frequently, an as yet unidentified post culture is emerging already now, in front of our eyes. It is the consequence of recent increasingly vital counterculture, forming since the Renaissance. From the end of the 1960s counter-culture has been contesting culture and challenging its sense. Nonetheless, it was incapable of creating permanent values on its own, because it had lost most of its energy while undermining the poor substitutes created by culture: “the religion of science”, “the religion of politics”, and “the religion of art”. Post culture is not directed against culture and counterculture, nor is it situated beyond their range. It does not negate values but renders them indelible and creates new ones. It carefully chooses from the residues of culture and counterculture. It reaches for the roots – the all-embracing sacrum. This is a culture undergoing transformations, a culture of numerous resignations and humility. It is not a culture of great slogans and undertakings, but of ideas and activities ostensibly inconsequential and scattered. A spontaneous form of self-defence against the ultimate decline of the most precious values. It is not tantamount to an attractive disassembly of the old or a brilliant construction of the new but comprises a laborious clearing of rubble and reconstruction on preserved foundations. New edifices will rise – but we shall find their main outlines familiar. Seeing them will not come as the sort of shock we sense while looking at super-modern and mighty constructions but will produce relief and a feeling of security, the same that we experience when, after many years of haste and travels, we finally stand in front of our family home. Just as Daniel Bell predicted, this will be a culture of a turn towards the past and tradition, a revival of memory, a culture of settling accounts and restrictions. There will also take place a great renascence and progress of the family, which will enable every person, together with those closest to him, to reveal and realise his creative activity in all its forms. Furthermore, it will also permit to boldly create one’s distinctness and to build personal identity and self-esteem. The path leading towards post culture can be described as a “third way” between the sacred and the profane; at the same time, it is precisely along this way that the sacred, descending into daily life, encounters the latter’s defiled version, which wishes to reach the level of sanctity. A path running between the church and the public office, between the roadside shrine and the community centre. Simultaneously, it is neither one nor the other: it remains in between and both links and divides. Lucim is a mediaeval village whose centre is encircled by a country road. This is precisely our third way, into which the country road changes from year to year. In everyday time it remains an ordinary road serving the purposes of daily bustle, but during the holidays it “soars upwards” while assuming a festive, ceremonial character.

Journal: Konteksty

- Issue Year: 327/2019

- Issue No: 4

- Page Range: 71-77

- Page Count: 7

- Language: Polish

- Content File-PDF