Vize socialistického mesta na príkladu Nové Ostravy

The vision of the socialist city on the example of Nová Ostrava

Author(s): Eva ŠpačkováSubject(s): Fine Arts / Performing Arts

Published by: Historický ústav SAV, v. v. i.

Keywords: Socialist Realism; sorela; Poruba; Nová Ostrava;post-war housing;industrial city; planned socialist city

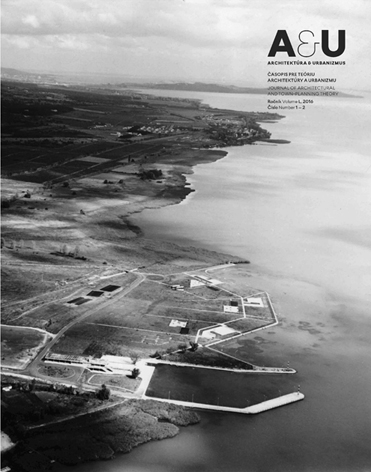

Summary/Abstract: Nová Ostrava, later called Ostrava-Poruba, is the most notable example of a new industrial city founded and constructed in the period of early socialism in Czechoslovakia after World War II. The particular mode of architectural forms, which is strongly evident in the plans of the new city and significantly affected its initial part constructed between 1951 – 1956, was already, at the time of its creation, known Socialist Realism. The architecture of Czechoslovakia in the first half of the 1950s has still not been clearly evaluated and accepted, even though it has already become in some cases the subject of heritage conservation. Contradictory views are also encountered in the scholarly evaluation of Socialist Realism, and its inclusion in the development of Czechoslovak and European architecture from the beginning of this debate post1989. As an important industrial hub of Czechoslovakia, the city of Ostrava was significantly damaged by military action at the end of World War II. After the war, it was necessary to repair and complete the missing ats quickly, yet also to replace the substandard housing in the workers’ colonies of many industrial plants. Gradually, the spontaneous construction of residential houses in the vicinity of factories gave way to strict construction plans of housing estates located outside the polluted industrial environment and coal reserves. This trend, based on the functionalist foundations laid out in the Athens Charter, eventually prevailed and established the requirement for a clear separation of housing from heavy industry. For decades now, this trend has shaped the face of the city, addressing part of the city’s problems at the time of construction yet also generating new problems to be faced by today’s generation. The first completed construction of new ats located according to plan in appropriate locations of the city was represented by the Model Housing Estate Belský les, where work began in 1946. The housing estate was supposed to be built within a two-year plan and serve as a model for other housing estate projects. Its concept was derived from the prewar tradition of functionalist urban planning and the specific architectural design of individual buildings. After 1950, the amount of construction was limited and the design projects for additional buildings were already in uenced by Socialist Historicism. The estate was never fully completed in accordance with the original plan. It should be mentioned that plans to move the residential part of the city of Ostrava to a new location outside the area affected by coal mining were first recorded in 1946. However, it was only under the communist regime, which completely took over the government after 1948, that the idea arose of b uilding a new socialist city for 150,000 inhabitants, intended to serve as a symbol of success and a showcase of the Socialist regime. Construction began on Nová Ostrava in the early 1950s in a location with favourable natural conditions to the northwest of the historic centre of Ostrava, in the former independent municipality of Poruba. Today, this locality (now OstravaPoruba) is one of Ostrava’s districts, with a population no greater than 70,000 inhabitants. Over a construction period of twelve years, the plan assumed the construction of a modern Socialist city, based along a representative main boulevard starting from the Svinov railway station and ending with the university building. Its architecture is associated with the vision of a new socially just society, where the workers, farmers and ‘labouring intellectuals’ collectively work together and utilize the fruits of their labour. Collectivization and subordination of the individual to a vision of a happy future formed the prerequisites for the creation of a new social order. The first simple fourstorey blocks of ats in the area of the temporary Mining Housing Estates still represent the final effort of prewar functionalism. After 1948, the architectural style gradually changed under pressure from Communistoriented architects, Soviet models, and communist rhetoric. Architecture was expected to be comprehensible to a wide audience, and to articulate the motto “socialist by content, national by form” to a broad audience. In addition, it was expected to refer to certain “progressive” historical periods in the Czech context, especially to the Renaissance and elements of folk architecture. The group of architects participating in the project of the new city’s urban design was led by the ambitious Vladimír Meduna. As for the gradual preparation of the architectural plans for Poruba, the task was assigned to the architects who were forced to leave their own private businesses and join the unified design organization Stavoprojekt. Individual buildings designed in Poruba, and therefore designed by the architects from Stavoprojekt, were also constructed in Ostrava, Prague and Brno. Starting in 1952, the first and most architecturally noteworthy part of Poruba began to be constructed based on the urban scheme of the dominant boulevards with monumental residential buildings and shop parterres...Nová Ostrava, later called OstravaPoruba, is the most notable example of a new industrial city founded and constructed in the period of early socialism in Czechoslovakia after World War II. The particular mode of architectural forms, which is strongly evident in the plans of the new city and significantly affected its initial part constructed between 1951 – 1956, was already, at the time of its creation, known Socialist Realism. The architecture of Czechoslovakia in the first half of the 1950s has still not been clearly evaluated and accepted, even though it has already become in some cases the subject of heritage conservation. Contradictory views are also encountered in the scholarly evaluation of Socialist Realism, and its inclusion in the development of Czechoslovak and European architecture from the beginning of this debate post1989.As an important industrial hub of Czechoslovakia, the city of Ostrava was significantly damaged by military action at the end of World War II. After the war, it was necessary to repair and complete the missing ats quickly, yet also to replace the substandard housing in the workers’ colonies of many industrial plants. Gradually, the spontaneous construction of residential houses in the vicinity of factories gave way to strict construction plans of housing estates located outside the polluted industrial environment and coal reserves. This trend, based on the functionalist foundations laid out in the Athens Charter, eventually prevailed and established the requirement for a clear separation of housing from heavy industry. For decades now, this trend has shaped the face of the city, addressing part of the city’s problems at the time of construction yet also generating new problems to be faced by today’s generation.The first completed construction of new ats located according to plan in appropriate locations of the city was represented by the Model Housing Estate Belský les, where work began in 1946. The housing estate was supposed to be built within a twoyear plan and serve as a model for other housing estate projects. Its concept was derived from the prewar tradition of functionalist urban planning and the specific architectural design of individual buildings. After 1950, the amount of construction was limited and the design projects for additional buildings were already in uenced by Socialist Historicism. The estate was never fully completed in accordance with the original plan. It should be mentioned that plans to move the residential part of the city of Ostrava to a new location outside the area affected by coal mining were first recorded in 1946. However, it was only under the communist regime, which completely took over the government after 1948, that the idea arose of b uilding a new socialist city for 150,000 inhabitants, intended to serve as a symbol of success and a showcase of the Socialist regime. Construction began on Nová Ostrava in the early 1950s in a location with favourable natural conditions to the northwest of the historic centre of Ostrava, in the former independent municipality of Poruba. Today, this locality (now OstravaPoruba) is one of Ostrava’s districts, with a population no greater than 70,000 inhabitants.Over a construction period of twelve years, the plan assumed the construction of a modern Socialist city, based along a representative main boulevard starting from the Svinov railway station and ending with the university building. Its architecture is associated with the vision of a new socially just society, where the workers, farmers and ‘labouring intellectuals’ collectively work together and utilize the fruits of their labour. Collectivization and subordination of the individual to a vision of a happy future formed the prerequisites for the creation of a new social order.The first simple fourstorey blocks of ats in the area of the temporary Mining Housing Estates still represent the final effort of prewar functionalism. After 1948, the architectural style gradually changed under pressure from Communistoriented architects, Soviet models, and communist rhetoric. Architecture was expected to be comprehensible to a wide audience, and to articulate the motto “socialist by content, national by form” to a broad audience. In addition, it was expected to refer to certain “progressive” historical periods in the Czech context, especially to the Renaissance and elements of folk architecture. The group of architects participating in the project of the new city’s urban design was led by the ambitious Vladimír Meduna. As for the gradual preparation of the architectural plans for Poruba, the task was assigned to the architects who were forced to leave their own private businesses and join the unified design organization Stavoprojekt. Individual buildings designed in Poruba, and therefore designed by the architects from Stavoprojekt, were also constructed in Ostrava, Prague and Brno.Starting in 1952, the first and most architecturally noteworthy part of Poruba began to be constructed based on the urban scheme of the dominant boulevards with monumental residential buildings and shop parterres. The boulevards were supposed to divide the city into individual parts, each with a structure created by semiopen blocks of ats, forming more intimate spaces of internal streets and yards. What was important for the overall impression were the corridor streets and boulevards. A number of squares were also planned, yet their role was not very important. Much attention was given to the commercial and cultural facilities. Shops were exclusively located on the street level of residential buildings oriented toward the main boulevard, thus making it a shopping promenade.Public administrative and political buildings, marked by distinctive towerlike forms, were intended to serve as the primary landmarks. However, none of these planned monumental buildings were ultimately built. The city’s architecture of Socialist Realism, called sorela in the Czech environment, was based on standardized units (types of layouts and constructions of blocks of ats) placed in a traditional classicist urban composition of a visually unified character, with emphasis on axial and symmetrical orientation. The decoration of the facades played an important role. Decorative elements were created through the fitting of prefabricated units onto the smooth facades of standardized blocks. The entire architectural impression is complemented with art works on the theme of labour, abundance and joyful life. Artworks appear on the house facades and also complement the public space.The basis of the layout of the residential buildings is formed by repeating standardized sections. Where the shape of the building was altered to create a fitting architectural expression, the ats were atypically designed and in some cases above the standard size. The architecture was formally exteriorfocussed only and the internal layout and appearance of the interior directly adhered to the prewar functionalist approach to housing, particularly in its requirement of a rational ground plan and furnishings with basic sanitary and operating facilities. The aesthetic of sorela had no significant in uence on the interior furnishing of the ats.Architects abandoned the forced style of sorela with its traditionalist, almost archaic, facade decorations in the aftermath of external pressure following the ending of the Stalinist ‘cult of personality’. Indeed, as early as 1955 the architects were criticized for the use of unnecessary and expensive decorations that increased construction costs.In other projects in the second half of the 1950s, the architects of Czechoslovakia returned to the architecture of the late international style. A return to modern architecture is associated with the success of Czechoslovakia’s participation at EXPO 1958 in Brussels. In the form of furniture design, household objects and industrial design, this style became quite popular and significantly affected the nation’s housing culture.According to the original master plan for Poruba, other sections were later built along the Main Boulevard (in Czech Hlavní trída), which preserved its character of a city boulevard. However, the buildings no longer bore the same historicist decorations, but instead consisted of standardized blocks constructed using the gradually emerging technology of prefabricated concrete panels. At the beginning of the Sixties, it was obvious that the concept of Nová Ostrava as an independent model Socialist city would remain unfulfilled. In locations where additional boulevards and imposing landmarks were supposed to be built, typical housing development started. Architects had always worked with standardized objects fitted, depending on the technological possibilities, into the green spaces, yet now freestanding blocks of ats, entirely lacking a street parterre and a traditional city street, had been replaced with freely owing space. Nor did the construction of prefabricated panel blocks ever completely satisfy the requirements for new ats, as expected by its promoters. After 1989, the construction of panel ats ended. Today, the city district of Poruba, and in particular its oldest area built in the 1950s, is among the most popular places to live in Ostrava. Today’s young generation sees the architecture that represented one of the attempts to utilize architecture as an ideological propaganda tool of totalitarian power outside of its ideological context. The prewar generation of functionalist architects who, for a relatively short period of time, had to follow the formal dictates of the historicist concept of architecture, at least managed in Ostrava to create an attractive part of the city.The urban fabric from the earliest period of construction, the socalled sorela, is currently listed as an urban conservation zone. Buildings outside this zone, as well as details of public space that through utilitarian reconstructions have lost their connection with the character of the whole zone, are not protected at all. And tools are lacking to maintain the generally accepted quality, and to draw attention to the values t hat should be protected for future generations. Completely outside the existing area of interest is the controversial character of architect Vladimír Meduna, author of the Poruba concept. Although he spent all his life (1909 – 1990) in the state’s highest architectural positions and functions, his in uence on the Czechoslovak architecture of the 1950s has yet to be documented and evaluated.

Journal: Architektúra & Urbanizmus

- Issue Year: 50/2016

- Issue No: 1-2

- Page Range: 18-37

- Page Count: 20

- Language: Czech