TRANSFORMATIVE PACIFISM IN THEORY AND PRACTICE:

GANDHI, BUBER, AND THE DREAM OF A GREAT AND LASTING PEACE

TRANSFORMATIVE PACIFISM IN THEORY AND PRACTICE:

GANDHI, BUBER, AND THE DREAM OF A GREAT AND LASTING PEACE

Author(s): Andrew FialaSubject(s): Philosophy, History of Philosophy, Philosophical Traditions

Published by: Instytut Filozofii i Socjologii Polskiej Akademii Nauk

Summary/Abstract: Pacifists imagine a “great peace,” to borrow a phrase from Martin Buber. This great peace will uphold justice and respect for humanity. It will not efface difference or negate liberty and identity. The great peace will be a space in which genuine dialogue can flourish—in which we can encounter one another as persons, listen to one another, embrace our common humanity, and acknowledge our differences. The great peace is much more than the absence of war. It is holistic, organic, dialogical, and thick with human relation.The dream of the great peace runs aground on the reality of petty conflicts, dehumanizing institutions, selfishness, egoism, arrogance, murder, war, and psychopathology. While ordinary selfishness poses a mundane obstacle to the great peace, genocide appears to create a reductio ad absurdum argument against the dream of the great peace and against pacifism itself. Critics will argue that in extremis a pacifist would be either mad or immoral to remain committed to nonviolence. This idea has been explored by a number of critics who argue that pacifism is primarily for dreamers and idealists, who are not willing to do what is necessary to confront evil and atrocity in the real world.This paper argues that a moderate commitment to pacifism and nonviolence remains plausible despite the atrocity objection. Some may argue that the term “pacifism” is not applicable to a position that admits that there are exceptional cases in which violence can be justified. But as I have argued elsewhere, there are varieties of pacifism (Fiala, 2004; 2008; 2014a; 2014b). The type of paci-fism described here is transformational or transformative pacifism. Transformational pacifism is not absolutist in its rejection of violence, even though it offers a comprehensive critique of violence that aims at creating the great peace by changing the way we think and talk about war, violence, and peace itself. Mar-tin Buber is a good example of a transformational pacifist. He admitted that some form of violence could be justified (say, in response to the Holocaust). But his goal was not to justify violence—rather, he wanted to transform the world in order to prepare the way for the great peace. One important considera-tion here is that Buber is not primarily a political thinker or an applied ethicist: rather, he offers a metaphysical, religious, psychological, and cultural theory. Transformative pacifism is located at that higher level. It idealizes, speculates, and imagines. For this reason, critics might condemn it as utopian. But trans-formative pacifism remains inspiring and useful.

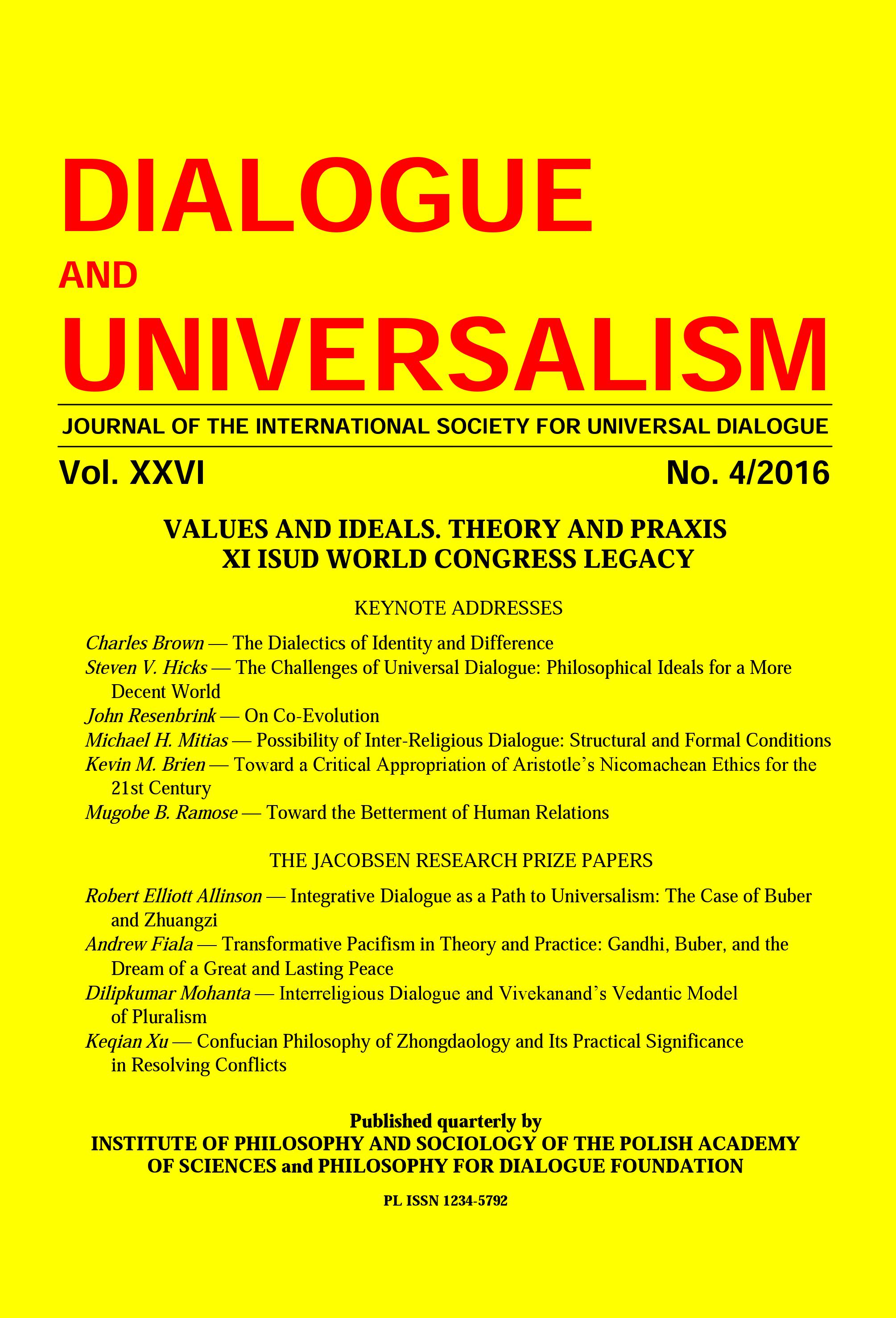

Journal: Dialogue and Universalism

- Issue Year: 2016

- Issue No: 4

- Page Range: 133-148

- Page Count: 16

- Language: English

- Content File-PDF