Autonomie et distraction

Autonomy and Distraction

Author(s): Eric MichaudSubject(s): History, Philosophy, Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Cultural history, Architecture, Visual Arts, Aesthetics

Published by: Институт за изследване на изкуствата, Българска академия на науките

Summary/Abstract: The history of the so-called ‘historical’ avantgardes, during the second half of the XXth century, was the object of a specific reinterpretation: their revolutionary aspirations, - formulated since 1910, both by the works of art and by the theoretical texts, and later supported by the political and social European revolutions-, would have made of them the victims of all the returns to the political order. The formal freedoms recently acquired, and that made of art a ‘hope of happiness,’ would have then come into contradiction with the constraints of the social field in which they had emerged. Therefore, art became ‘the promise of a happiness which breaks up’, as Adorno claimed in his Aesthetic Theory at the end of the 1960ies. During the 1990thies, the idea of a ‘failure’ of the avantgardes became increasingly accepted (Eric J. Hobsbawm, T. J. Clark). Confronted by the over- whelming power of an economical and ideological ‘system,’ according to this interpretation, art would have been condemned to either compromises or ‘recuperations’ that would necessarily neutralize its subversive challenge. Now, all these claims were grounded on the certitude that art, during its historical development, had acquired its ‘autonomy’. But how should we understand ‘autonomy’? At least five different meanings have emerged since the beginning of the XIXth century. The first referred to the emancipation of the liberal arts, or Fine Arts, from the mechanical arts that had occurred since the Renaissance. The second meaning of the autonomy of art implied that it was emancipated from the authority of religious and political powers and coupled this progressive liberation with that of the individual subject. The ‘unlimited freedom’ granted to art sanctioned the fact of its entry into the highly competitive realm of the market economy. While, almost at the same time, appeared the idea that art was independent of its historical and social conditions: the theory of l’art pour l’art. The theory of the work of art as a pure monad thus answered the one of a social art, advanced in France and Europe by the Saint-simoniens who wanted the task of art to be the one realizing the Golden Age on Earth. A fourth conception of the autonomy of art was more formalistic: it celebrated, since the end of the 19th century, the divorce of art from the classical tradition of mimesis and its quest for its own laws. To this conception was linked a last one, according to which artistic activity and its productions were absolutely independent from the public and the conditions of reception. If all these acceptations of the autonomy of art are to be found in Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory, then this last was elaborated already in the 1930thies at the time of the debate that opposed Adorno to his friend Walter Benjamin on the occasion of Benjamin’s essay on the Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility. Benjamin’s theses were anthropological rather than political. For him, ever since art had been detached from a magical or religious cult, seeming to thereby affirming its autonomy, its objects no longer demanded meditation or contemplation. These objects produced their effect in distraction, or, better yet, in distracted use. But these fabricated objects, giving their rhythm to the minute rituals of everyday life, conserved for art its own essential function of humanity’s self-instigation and training. A humanity increasingly exposed to the dangers provoked by modern life would secrete an art capable of preparing men for yet newer dangers. Adorno’s theses on the relative autonomy of art, which would found his Aesthetic Theory and would rephrase in their own terms the dominant discourse of these 30 years, were evidently in complete opposition with the anthropological conception that Benjamin defended and which implied the dissolution of the classical concept of art as a socially separated activity. To Adorno’s pessimist and lofty vision, Benjamin opposed in advance the precise and technical observation of the transformations of the mimetic comportment that operated before his eyes and, after the age of gods, succeeded in destroying the age of art.

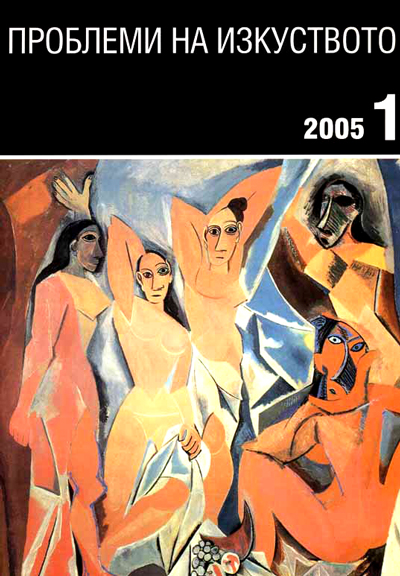

Journal: Проблеми на изкуството

- Issue Year: 2005

- Issue No: 1

- Page Range: 7-14

- Page Count: 8

- Language: French

- Content File-PDF