Neskorý modernizmus v prostredí slovenských kúpelov

Late modernism in the Slovak spa localities

Author(s): Martin ZaičekSubject(s): Fine Arts / Performing Arts

Published by: Historický ústav SAV, v. v. i.

Keywords: Slovak spa towns; spa architecture; late modernism; Zdravoprojekt; Slovakoterma Bratislava; Curative house; sanatorium

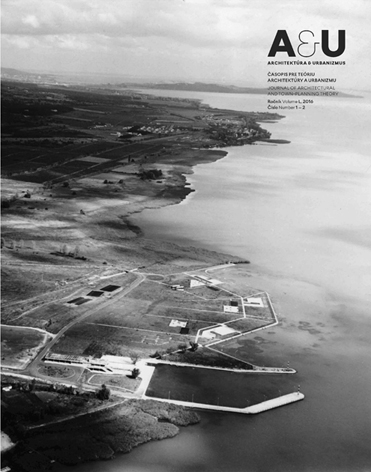

Summary/Abstract: Though small in size, Slovakia is rich in its springs of natural healing water. These springs are an important precondition for the development of the spa as a social institution, yet natural resources alone cannot provide all the services of a spa. For the providing of therapy, what is necessary is a complex of balneology and sanatoriums, which together with the natural surroundings create the spa environment. In the second half of the 20th century, Slovak spa localities were the setting for massive construction development, intended to improve Slovakia’s spas to the level of the best world quality. As a consequence, we can observe here several dozen complexes of realized objects, build in the aesthetics of late modernist architecture, most of which are still in use in the original form and provide a crucial part of the spa services in Slovakia. The spa development from the period of the 1960s to the 1980s was both a €nancially and technically complicated process, organized by the centralized spa organization Slovakoterma Bratislava, a state enterprise forming an important partner to the design institute Zdravoprojekt, itself responsible for the design of most of the realized post war concepts in Slovak spa localities.In 1948, political power in Czechoslovakia was seized by the Communist Party. In the same year, new legislation was introduced by which all natural resources, including natural springs, were nationalized. All spa localities become the part of the company Czechoslovak State Spas and Springs. In the following years, the spa locality was described by the new legislation as a place for health rehabilitation. For the €rst time, Slovak spas became a part of the institutionalized curative – prevention health care system. In addition, shortly before the communist revolution, in 1947 a special balneological congress was held in Štrbské Pleso in the High Tatras, where it was decided to divide all approximately 50 Slovak spa localities into categories of importance and indication groups. According to this plan, 3¨categories were created: 1. spa of international importance, 2. spa of national importance and 3. spa of local importance. Only the spas of Categories I and II received further development as part of the curative health system.Up until the 1960s, there was no new construction development, though all former spa hotel facilities were reconstructed into a hospital type of accommodation in the process called “dehotelization” of the spa.During this time the new legislative background and institutions of the control and management of the spa were created as well. In the early 1950s, the institution of an inspectorate for the preservation of natural curative spas and natural healing resources was set up which, along with Slovakoterma (the directorate of Czechoslovak state spas and springs in Bratislava) was given responsibility for the upcoming construction development in all the spa localities.In 1966 a specialized state design institute was founded, Zdravoprojekt Bratislava (“health – project”) which from the very beginning had a speci€c branch, Studio 03, responsible for the architectural design for the state spas. The director and founding architect Viktor Uhliarik put together a team of several dozen architects, including Richard Pastor, Ján Fibinger, Jaroslav Vítek as well as the recent graduates Jozef Schuster and Christo Tursunov. For the next 26 years of the existence of Zdravoprojekt, these architects became the leading personalities, whose architectural ideas were realized in many built objects of health care infrastructure and spa recreation.With these conditions in place the centralized management of spa localities, new legislation and the good economic situation in the 1960s – a plan was introduced for further spa development. During the next two decades, groups of sanatoriums, balneology, cultural and other spa infrastructure were realized in 14 localities of category I and II spas out of 22 registered spa localities.The principles of the postwar spa development and architectural creation emerged in Slovak discourse based on local and foreign references. Architect Jaroslav Vítek summarized them in the study analysis of spa development (1981). The main principles of urban and architectural planning in spa localities were: a) respecting the local natural and cultural context of the spa locality; b) creation of pedestrian zones in the spa that could interact with the local urban structure and natural surroundings based upon the general traf€c plan; c) ensuring that new construction developments are suitable for the yearround use of the spa and appropriate for the creation of the valuable spa environment. Development should be planned in separate construction phases, a factor that stressed the idea of a longterm conception of spa development.Among the €rst localities where the new development started was Bardejov. Though an important spa locality, it lacked the development of previous spa infrastructure in comparison to, e.g., Pieštany or Trencianske Teplice. In 1966, work started on the design of the new balneology centre (V. Uhliarik, J. Schuster), which was also the €rst design commission assigned to Zdravoprojekt Bratislava, newly established in the same year. Shortly after, development continued with the spa colonnade designed by the same authors and the new sanatorium Ozón designed by Schuster alone. Pieštany’s Spa Island was a special locality where the total volume of investments far exceeded those of all other spa localities. The initial project for the present Balnea Center was designed as early as the start of the 1960s by architect A. Placko who with his colleague P. Kárdoš also designed at the same time the €rst plan for future development of the Spa Island. In this plan, the idea was to build smallerscale sanatoriums and balneology complexes in the form of separate pavilions spread throughout the island. Placko’s and Uhliarik’s Balnea Palace (1966) as the €rst postwar sanatorium in the locality was later joined by the Balnea Grand and Splendit (V.¨Uhliarik, J.¨Schuster, 1971) and Balnea Esplanade (V. Uhliarik, Ch. Tursunov, 1980). This complex is the biggest spa structure in the country.Between the years 1970 – 1980, a tendency began to appear in Slovak architectural creation towards greater sculptural articulation and division of the architectural volumes. Plasticity of architecture was, according to the era’s architects, more suitable for the communication of the form with the existing urban structure as well as the spa environment because it minimized the monumentality of the objects. The abstraction of form was a pronounced characteristic of Slovak architecture, which at that time used form to celebrate symbolically the increasing democratic changes in the society. After the political thaw in the end of the 1960s, architects became more courageous to implement western progressive architectural features into their work. In most of the realized objects, the monumental character is given less by the language of architecture than instead by a consequence of the program and typology. Usually, the sanatoriums were built with a 250bed capacity at the hotel standard “A”, and included within themselves as well additional spa and treatment facilities. Development and research relating to the typology of the spa building was one of the tasks assigned to Zdravoprojekt.Since 1989, the formerly institutionalized spa recreation has been in the process of being replaced by a hotel type of recreation. This process has had a direct impact on the original form and function of late modern spa architecture, in which material appearance and architectural detail are signi€cantly altered or destroyed. The greatest victim of such a transformation is the former sanatorium Helios in High Tatras (arch. Richard Pastor, 1966 – 1976) which according to the plans for its reconstruction into a hotel was partly demolished and remained abandoned. Technical adaptation and energy optimization caused the lost of original materiality when the stone facade cladding was replaced by a Styrofoam façade, as in the case of the Krym sanatorium in Trencianske Teplice or Sanatorium Polana in Brusno.The objects for spa recreation in Slovakia did not emerge easily. The process of the design and construction was a longterm issue and demanded enormous investments. The ambitious was at least to develop spa localities to the level of the standards and quality of Czech spas, in other words to an international high quality standard. In this context, the discussed period of spa development formed part of the cultural emancipation of Slovakia within the Czechoslovak federation. The Slovak spa complexes built between 1960 and 1990 have the potential to become attractive not only for the spa recreation itself, but for architecture as well.

Journal: Architektúra & Urbanizmus

- Issue Year: 50/2016

- Issue No: 1-2

- Page Range: 56-75

- Page Count: 20

- Language: Slovak